ESTUDIOS / RESEARCH STUDIES

THE INQUISITORIAL CENSORSHIP OF AMATUS LUSITANUS CENTURIAE

Isilda Rodrigues

University of Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro

isilda@utad.pt

ORCID iD: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6020-5767

Carlos Fiolhais

University of Coimbra

tcarlos@uc.pt

ORCID iD: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1527-0738

ABSTRACT

We analyse the inquisitorial censorship expressed in expurgations of some excerpts of the Centuriae of Medicinal Cures, authored by the Portuguese physician João Rodrigues de Castelo Branco (1511-1568), better known as Amatus Lusitanus. Our sources were the Centuriae II, III and IV (bound together, Florence, 1551) and the Centuria VII (Venice, 1566), both kept in the General Library of the University of Coimbra, Portugal. For the reconstitution of the texts we resorted to other editions available online and to the modern Portuguese translation, prepared from the Bordeaux edition of 1620. We conclude that most of the censored excerpts refer to affections of sexuality, gynaecology and obstetrics, the remaining being related to matters of strictly religious nature.

LA CENSURA INQUISITORIAL EN LAS CENTURIAS DE AMATUS LUSITANUS

RESUMEN

En este artículo analizamos la censura inquisitorial expresada en expurgaciones de algunos extractos de Centurias de Curas Medicinales, escrito por el médico portugués João Rodrigues de Castelo Branco (1511-1568), más conocido como Amatus Lusitanus. Nuestras fuentes han sido las Centurias II, III y IV (atadas juntas, Florencia, 1551) y Centuria VII (Venecia, 1566), ambas conservadas en la Biblioteca General de la Universidad de Coimbra, Portugal. Para la reconstitución de los textos recurrimos a otras ediciones disponibles online y a la nueva traducción portuguesa, preparada a partir de la edición de Burdeos de 1620. Concluimos que la mayoría de los extractos censurados se refieren a afecciones de sexualidad, ginecología y obstetricia, el resto se relacionan con asuntos de naturaleza estrictamente religiosa.

Received: 07-03-2017; Accepted: 09-07-2018.

Cómo citar este artículo/Citation: Rodrigues, Isilda; Fiolhais, Carlos (2018), "The inquisitorial censorship of Amatus Lusitanus Centuriae", Asclepio, 70 (2): p229. https://doi.org/10.3989/asclepio.2018.13

KEYWORDS: Amatus Lusitanus; Centuriae; Censorship; 16th century; Medicine.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Amatus Lusitanus; Centurias; Censura; siglo XVI; Medicina.

Copyright: © 2018 CSIC. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.

CONTENTS

AMATUS LUSITANUS AND THE CENTURIAE Top

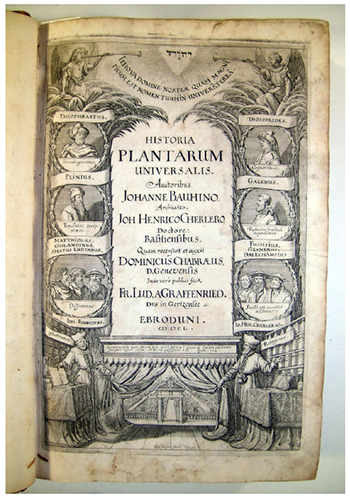

João Rodrigues de Castelo Branco (1511-1568), the Portuguese Jew who signed his works with the name Amatus Lusitanus, was one of the greatest figures of medicine of the 16th century (Guerra, 1989Guerra, Francisco (1989), Historia de la medicina, 1, Madrid, Ediciones Norma, S.A., pp. 294-310.; Rodrigues and Fiolhais, 2013Rodrigues, Isilda and Fiolhais, Carlos (2013), "O ensino da medicina na Universidade de Coimbra no século XVI", História, Ciência e Saúde – Manguinhos, 20 (2), pp. 435-456.). Recognized in life, his fame continued posthumously as shown by the publication of his face along with those of other famous doctors such as Dioscorides, Pliny and Galen in the frontispiece of the Historia plantarum universalis[1] by the Swiss botanists and physicians Johann Bauhin (1541-1612) and Johann Heinrich Cherler (1570-1610) (Figure 1). Having lived most of his life in exile, errant in territories which belong today to the Belgium, Italy, Croatia and Greece, his services were requested by notables as great and diverse as the Pope, the king of Poland, the authorities of the city-state of Ragusa (nowadays Dubrovnik) and the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. His intellectual capacity and his knowledge of medical and pharmacological matters were so wide that he appeared often confronting not only classic authors, but also prominent contemporary peers like, including Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), the Belgian Professor of Anatomy at the University of Padua, author of De Humani Corporis Fabrica[2], who is considered the founder of modern medicine (Rodrigues and Fiolhais, 2015Rodrigues, Isilda and Fiolhais, Carlos (2015), "Amato Lusitano na cultura científica do seu tempo – Cruzamentos com Vesálio e Orta", Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de História da Ciência, 8 (1), pp. 79-88, Accessible at: https://estudogeral.sib.uc.pt/bitstream/10316/40734/1/Isilda%20Rodrigues_Carlos%20Fiolhais.pdf (retrieved on 04/10/2016).).

|

Figure 1. Cover of Historia plantarum universalis, by Johann Bauhin and Johann Heinrich Cherler. Amatus face appears in a medallion in the left hand side, below, together with those of Pietro Andrea Mattioli or Matthiolus (1500-1577) and Guillandinus, with the subtitle “Dissentimus” (“we disagree”, a reference to a violent polemic between Amatus and Mattioli; Guimarães,(2013)

[Descargar tamaño completo]

| |

The work of Amatus has been studied by many researchers. Among the non-Portuguese authors who published works on him we list, not being exhaustive, in chronological order: Max Salomon (1901Salomon, Max (1901), Amatus Lusitanus und seine Zeit. Ein Beitrag sur Geschichte der Medizin im 16. Jahrhundert, Sonderabdruck der Zeitschrift für Klinische Medizin, vols. 41-42, Berlin, reimp. Nabu Press, 2010. Accessible at: https://archive.org/details/b2900813x (retrieved on 18/10/2016).), Harry Friedenwald (1937Friedenwald, Harry (1937), "Amatus Lusitanus", Bulletin of the Institute of History of Medicine, 5, pp. 603-653., 1955Friedenwald, Harry (1955), "Medical works of Amatus Lusitanus". In: Homenagem ao Doutor João Rodrigues de Castelo Branco (Amato Lusitano), Castelo Branco, Câmara Municipal, pp. 177-191.), Pietro Capparoni (1941Capparoni, Pietro (1941), "Amato Lusitano e la sua testimonianza della scoperta delle valvole delle vene fatta da G. B. Canano", Atti e Memorie dell’Accademia di Storia dell’Arte Sanitaria, appendice alla Rassegna di Clinica, Terapia e Scienze affini, Anno XL (Fasc. 4), Luglio-Agosto.), Joshua Otto Leibowitz (1953Leibowitz, Joshua Otto (1953), "A probable case of peptic ulcer described by Amatus Lusitanus", Bulletin of the History of Medicines, 27, pp. 212-216., 1958Leibowitz, Joshua Otto (1958), "Amatus Lusitanus and the Obturator in Cleft Palates", Journal of the History of Medicine, 13, pp. 492-503., 1968Leibowitz, Joshua Otto (1968), "Amatus Lusitanus (1511-1568) à Salonique", Estudos de Castelo Branco, 28, pp. 90-93.), Jacob Seide (1955Seide, Jacob (1955), "The two diabetics of Amatus Lusitanus", Imprensa Médica, 19 (11), pp. 670-674.), Joseph Néhama (1955Néhama, J. (1955), "Amato Lusitano à Salonique". In: Homenagem ao Doutor João Rodrigues de Castelo Branco (Amato Lusitano), Castelo Branco, Câmara Municipal, pp. 213-214.), Hirsh Rudy (1931Rudy, Hirsch (1931), "Amatus Lusitanus", Archeion, 13, pp. 424-449., 1955Rudy, Hirsch (1955), Homenagem ao Doutor João Rodrigues de Castelo Branco (Amato Lusitano), Castelo Branco, Câmara Municipal, pp. 193-211.), Nick Spyros Papaspyros (1964Papaspyros, Nick Spyros (1964), The history of diabetes mellitus (2nd. ed.), Stuttgart, Georg Thieme.), Luigi Samoggia (1966Samoggia, Luigi (1966), "Aspetti del pensiero scientifico di Amato Lusitano", Pagine di Storia della Medicina, 10 (3), pp. 14-23.), Lavoslav Glesinger (1968Glesinger, Lavoslav (1968), "Amato Lusitano em Ragusa", Estudos de Castelo Branco, 28, pp. 158-178.), Hrvoje Tartalja (1985Tartalja, Hrvoje (1985), "Les médicaments qu’Amatus Lusitanus utilisait à l’occasion de son travail à Dubrovnik". In: Puerto Sarmiento, Francisco Javier, Farmacia e industrializacion. Homenaje al doctor Guillermo Folch Jou, Madrid, Sociedad Española de Historia de la Farmacia, pp. 237-246.), Maria Luz López Terrada and Vicente Salavert Fabiani (1999López Terrada, María Luz and Salavert Fabiani, Vicente L. (1999), "Le médecin de la Renaissance à l’aube des Lumières". In: Callabert, Louis (dir.), Histoire du médecin, Paris, Flammarion, pp. 143-150.), Lycurgo Santos Filho (1991Santos Filho, Lycurgo de Castro (1991), História Geral da Medicina Brasileira, vol. 1, São Paulo, HUCITEC Editora.), Dov Front (1998Front, Dov (1998), "The Expurgation of the Books of Amatus Lusitanus", Book Collectors, 47, pp. 20-36., 2001Front, Dov (2001), "The expurgation of medical books in sixteenth-century Spain", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 75 (2), pp. 290-296.), Marija-Ana Dürrigl and Stella Fatovic-Ferencic (2002Dürrigl, Marija-Ana and Fatovic-Ferencic, Stella (2002), "The medical practice of Amatus Lusitanus in Dubrovnik (1556-1558) a short reminder on the 445th anniversary of his arrival", Acta Médica Portuguesa, 15, pp. 37-40.), Jurica Bacic et al. (2002Bacic, Jurica; Vilovic, Katarina and Baronica, Koraljka Bacic (2002), "The gynaecological-obstetrical practice of the renaissance physician Amatus Lusitanus (Dubrovnik, 1555-1557)", European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 104 (2), pp. 180-185.), Alfredo Pérez Alencart (2005Pérez Alencart, Alfredo (2005), "Descubrimiento de Amato Lusitano", Medicina na Beira Interior. Da Pré-História ao Século XXI — Cadernos de Cultura, 19, pp. 40-41.), and Michal Altbauer-Rudnik (2009Altbauer-Rudnik, Michal (2009), Prescribing Love: Italian Jewish physicians writing on lovesickness in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Jerusalem, European Forum at the Hebrew University.). The Portuguese literature on him is vaster: an updated reference is the recent compilation of works done by João Rui Pita and Ana Leonor Pereira (2015Pita, João Rui and Pereira, Leonor (2015), "Estudos contemporâneos sobre Amato Lusitano". In: Andrade, António; Mora, Carlos and Torrão, João (coords.), Humanismo e Ciência, Antiguidade e Renascimento, Aveiro, Universidade de Aveiro Editora, pp. 513-541.). Some new publications appeared associated to the celebration, held in 2011, of the 5th centenary of Amatus birth (Morais, 2011Morais, João Augusto David de (2011), Eu, Amato Lusitano. No V Centenário do seu Nascimento, Lisboa, Edições Colibri. and Caderno, 2012[3]). A recent academic project which focused on his botanical works, namely comments on Dioscorides, gave rise to two volumes containing various contributions coordinated by António Andrade et al. (Andrade et al., 2013Andrade, António; Torrão, João; Costa, Jorge and Costa, Júlio (coords.), (2013), Humanismo, Diáspora e Ciência, séculos XVI e XVII, Porto, Universidade de Aveiro e Biblioteca Pública Municipal do Porto, https://doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-0945-4. and 2015Andrade, António; Mora, Carlos and Torrão, João (eds.), (2015), Humanismo e Ciência, Antiguidade e Renascimento, Aveiro, Universidade de Aveiro Editora e Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, pp. 513-541, [online], https://doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-0941-6.). From the same author see also two recent papers on aspects of the troubled Amatus biography (Andrade, 2010Andrade, António Manuel Lopes (2010), "Ciência, negócio e religião: Amato Lusitano em Antuérpia". In: Castro, Inês de Ornellas and Anastácio, Vanda (coords.), Revisitar os Saberes, Referências Clássicas na cultura portuguesa do Renascimento à época moderna, Lisboa, Centro de Estudos Clássicos, pp. 9-50. and 2012Andrade, António Manuel Lopes (2012), "Os inventários dos bens de Amato Lusitano, Francisco Barbosa e Joseph Molcho, em Ancona, na fuga à Inquisição (1555)", Ágora. Estudos Clássicos em debate, 14.1, pp. 45-90, Accessible at: http://revistas.ua.pt/index.php/agora/article/view/2268 (retrieved on 08/01/2015).).

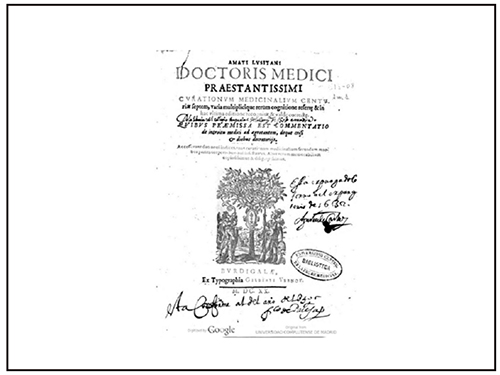

Amatus main work, the Curatiorum Medicinalium centuriae[4] (Figure 2) (”Centuriae of medical cures”), is a remarkable work of medicine of the 16th century, as shown by the large number of editions that followed the original ones (at least 57 editions are known of parts or of the whole work; Rodrigues, 2005Rodrigues, Isilda (2005), Amato Lusitano e as problemáticas sexuais – Algumas considerações para uma nova perspectiva de análise das Centúrias de Curas Medicinais, Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Ph.D. thesis.). The first one came out in Florence in 1551 and the seventh in Salonica in 1561. Each of the seven Centuriae holds one hundred clinical cases, as the title indicates. Each case, that Amatus called Cure (Curatio), presents the story of a patient and indicates the treatment selected according to the clinical picture observed by the author. The clinical evolution is described, in general accompanied by comments based on his extensive medical background. In these comments, the Portuguese doctor evokes several classical and contemporary authorities, discusses the effect of drugs and attributes the changes to treatments, depending on the characteristics of the patient and the progression of the disease. The range of topics of the Curatio is extremely vast, including anatomy, clinic, surgery, therapy, technical inventions, and new drugs, from preparation to administration.

|

Figure 2. Cover of the book Curationum medicinalium centuriae septem... quibus praemissa est commentatio de introitu medici ad aegrotantem, deque crisi & diebus decretorijs. (Burdigalae: Gilberti Vernoy, 1620). This posthumous edition encompasses all Centuriae. A note in the frontispice indicates that the book has been expurgated

[Descargar tamaño completo]

| |

The Centuriae belongs to the History of Science for the originality of its contents as well as for its well-thought organization. Amatus clearly deviates from the classic structure of the medical treatises of the epoch, adopting instead an organization of materials that will become common from the 17th century on: the style of a “logbook”, with no clear separation of topics, noting the cases of patients who come to doctors’ hands in all relevant aspects: diagnostic, therapy and result. His presentation style and language make this script of clinical cases a reference handbook that could be useful in discussions in academic and medical circles as well as to satisfy the curiosity and help expanding the knowledge of educated layers, if they could read Latin, the lingua franca of science at that time. The clear and detailed presentation shows the authors concern about informing different types of readers. Pedro Laín Entralgo (1989Laín Entralgo, Pedro (1989), Historia de la medicina, Barcelona, Salvat.) remarks that, in the 16th and 17th centuries, not only Amatus but various other European doctors cultivated a new medical literature genre, based on case narratives and more geared for understanding based on seeing and doing. Gianna Pomata calls this genre Observationes and stresses his historical relevance when she writes that “it had become a primary form of medical writing in the 18th century” (Pomata, 2010Pomata, Gianna (2010), "Sharing Cases: the Observationes in Early Modern Medicine", Early Science and Medicine, 15 (3), pp. 193-236.; Class, 2014Class, Monika (2014), "Introduction Medical Case Histories as Genre; New Approaches", Literature and Medicine, 32 (1), pp. VII-XVI.). On this issue it useful to see the discussion of the notebooks of the Swiss physician Georg Handsch (1520-1595), a contemporary of Amatus (Solberg, 2013Solberg, Michael (2013), "Empiricism in sixteenth-century medical practice: the Notebooks of Georg Handsch", Early Science and Medicine, 18 (6), pp. 487-516.).

Amato lived at a time when the Inquisition was increasing its influence in Southern Europe (Bethencourt, 1994Bethencourt, Francisco (1994), História das Inquisições: Portugal, Espanha e Itália, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores.; Marcocci and Paiva, 2013Marcocci, Giuseppe and Paiva, José Pedro (2013), História da Inquisição Portuguesa — 1536-1821, Lisboa, Esfera dos Livros.). It is well-known that the Centuriae have been at some point prohibited by the Inquisition (macrocensorship) and later authorized only after some expurgations, i.e., the erasement of selected excerpts (microcensorship). In the sequel of some recent works on the Inquisitorial macro and microcensorship (Front, 2001Front, Dov (2001), "The expurgation of medical books in sixteenth-century Spain", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 75 (2), pp. 290-296.; Baudry, 2012Baudry, Hervé (2012), "A censura dos livros de médicos portugueses. Descrição metodológica dos exemplares conservados nas bibliotecas da Universidade de Coimbra", Cultura. de História e Teoria das Ideias, 30, pp. 275-288.; Costa, 2013Costa, Júlio Manuel Rodrigues (2013), "Arte Médica: breve olhar sobre alguns impressos quinhentistas e seiscentistas da BPMP". In: Andrade, António; Torrão, João; Costa, Jorge and Costa, Júlio (coords.), Humanismo, Diáspora e Ciência, sécs. XVI and XVII, Porto, Universidade de Aveiro e Biblioteca Pública Municipal do Porto.), we analyse here the censorship suffered by this work in the Iberian Peninsula, on the basis of three copies of the Centuriae (II-IV, Florence, 1565[5]; VII, Lyon, 1565[6]; and I-VII, Bordeaux, 1620[7]) kept at the General Library of the University of Coimbra, Portugal (this historical library also owns the first Centuria of 1551[8]) comparing them with editions of the same books found elsewhere which apparently were not censored. We start by providing an overview of the Inquisitorial censorship of medical books, focusing in Spain and Portugal (both receiving influence from Rome, at a time marked by the Council of Trent), and continue analysing concrete cases of expurgations done in the Centuriae in the copies we have examined. We end up with some conclusions.

INQUISITORIAL CENSORSHIP OF MEDICAL BOOKS Top

The Inquisition or Tribunal of the Holy Office, established in Spain in 1478, in Portugal in 1536 and in Rome in 1542 played a relevant role in book censorship (Bethencourt, 1994Bethencourt, Francisco (1994), História das Inquisições: Portugal, Espanha e Itália, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores.; Martínez de Bujanda, 1995Martínez de Bujanda, Jesús (dir.) (1995), Index de l’Inquisition Portugaise, 1547, 1551, 1561, 1564, 1581, vol. 4 de Index des Livres Interdis, Sherbooke, Centre d'études de la Renaissance. and 2016Martínez de Bujanda, Jesús (2016), El Índice de libros prohibidos y expurgados de la Inquisición española (1551-1819), Madrid, Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos.; Baldini and Spruit, 2009Baldini, Ugo and Spruit, Leen (eds.), (2009), Catholic Church and Modern Science. Documents from the Archives of the Roman Congregations of the Holy Office and the Index, Roma, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, [Fontes Archivi Sancti Officii Romani].). The main target of the censors were not scientific works but theological, moral philosophical works. But censorship prevented, or at least tried to prevent (in fact, it did not was always very effective), the circulation of scientific works or excerpts of works, depending whether the decision was of total prohibition or mere expurgation. A reference in the Indices, the list of total or partially forbidden books of the Catholic Church, would lead a good catholic to avoid some authors since he was not even supposed to read their works. The circulation of the censored texts was extremely limited in the case of completely forbidden books but was also limited when some carefully chosen passages were expurged by the inquisitors. Even in least serious cases, where the books could continue to circulate after the omission of some excerpts, the discomfort of knowing that the author was suspicious was enough to inspire concern in many readers.

The first Roman Index came out in 1557 under Pope Paul IV, Index Auctorum et Librorum, with a more severe edition, appearing in 1559. After the Council of Trent, a new version, with the title Index Librorum Prohibitorum, was published in 1564, under Pope Pius IV. It contained several rules for intellectual control whose main motivation was to limit the Lutheran influence (Tarrant, 2014Tarrant, Neil (2014), "Censoring Science in sixteenth- century Italy: recent (and not-so-recent research)", History of Science, 52 (1), pp. 1-24.). In 1607, at the time of Paul V, an Expurgatory Index was published in Rome.

Although the Spanish King Charles V, head of a vast empire, promoted the publication of an Index in Louvain in 1546, in Spain only four editions of the Index were printed in the 16th century (1551, 1559, 1583, 1584), while six others appeared in the 17thand 18th centuries (1612, 1632, 1640, 1707, 1747 and 1790) (Bethencourt, 1994Bethencourt, Francisco (1994), História das Inquisições: Portugal, Espanha e Itália, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores.; Martins, 2011Martins, Maria Teresa Payan (2011), "O Índice Inquisitorial de 1624 à luz de novos documentos", Cultura. Revista de História e Teoria das Ideias, 28, pp. 67-87, Accessible at: https://cultura.revues.org/170 (retrieved on 16/02/2016).). The 1559 Index, in which ca. 700 books were censored, was published at the behest of Inquisitor Fernando de Valdés y Salas. The next two were published during the term of the Inquisitor Gaspar de Quiroga: the Index et Catalogus librorum prohibitorum, of 1583, with 2315 forbidden books, and the Index librorum expurgatorum, of 1584, which was innovative since the indication was now only to erase the parts considered pernicious. Some authors were totally banned, while others had only some works forbidden and, in the mildest version, had some excerpts expurged (Martins, 2011Martins, Maria Teresa Payan (2011), "O Índice Inquisitorial de 1624 à luz de novos documentos", Cultura. Revista de História e Teoria das Ideias, 28, pp. 67-87, Accessible at: https://cultura.revues.org/170 (retrieved on 16/02/2016).). In 1612 the Inquisitor Bernardo de Sandoval y Rojas published, in a single volume, a combined list of prohibited and expurgated books: Index Librorum Prohibitorum et Expurgatorum. Other Spanish indices followed that major work. Most of the banned books were printed out of Spain so that the Inquisition organised inspections at workshops, bookshops, libraries and ships entering the harbours to implemente its control (Bethencourt, 1994Bethencourt, Francisco (1994), História das Inquisições: Portugal, Espanha e Itália, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores.).

A study done by José Luis Peset Reig and Mariano Peset Reig (1968Peset Reig, Mariano and Peset Reig, José Luis (1968), "El aislamiento científico español a través de los índices del inquisidor Gaspar de Quiroga de 1583 y 1584", Anthologica Annua, XVI, pp. 25-41.) discussed the relationship between the inquisitorial censorship and Spanish science. José Pardo Tomás, in more detailed studies, remarked that in the 1559 and 1583 Spanish Indices respectively 8% and 7% of the works were scientific ones and pointed out that medicine was particularly affected by inquisitorial censorship in the 16th century (Pardo Tomás, 1983Pardo Tomás, José (1983), "Obras y autores científicos en los índices inquisitoriales españoles del siglo XVI (1559, 1583 y 1584)", Estudis: Revista de historia moderna, 10, pp. 235-260. and 1991Pardo Tomás, José (1991), Ciencia y Censura: La Inquisición Española y los libros científicos en los siglos XVI y XVII, Madrid, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.): roughly one third of the censored scientific works were on medical matters.

The censorship practice in Portugal followed closely that of Spain and also influenced it, both receiving inspiration from Rome (Bethencourt, 1994Bethencourt, Francisco (1994), História das Inquisições: Portugal, Espanha e Itália, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores.; Martins, 2011Martins, Maria Teresa Payan (2011), "O Índice Inquisitorial de 1624 à luz de novos documentos", Cultura. Revista de História e Teoria das Ideias, 28, pp. 67-87, Accessible at: https://cultura.revues.org/170 (retrieved on 16/02/2016).): in fact, there are striking similarities between some lists of banned authors, showing the religious exchange of the two Iberian countries (we should remind that the two crown were joined, in the so-called “dual monarchy”, from 1580 to 1640). Reference works on the Portuguese Inquisitorial censorship are Pereira (1976Pereira, Isaías da Rosa (1976), Notas históricas acerca de índices de livros proibidos e bibliografia sobre a Inquisição, Lisboa, Livraria Editora.), Rego (1982Rego, Raul (1982), Os índices expurgatórios e a cultura portuguesa, Lisboa, Instituto de Cultura e Língua Portuguesa.), Sá (1983Sá, Artur Moreira de (1983), Índices dos livros proibidos em Portugal no século XVI. Apresentação, estudo introdutório e reprodução fac-similada dos índices, Lisboa, Instituto Nacional de Investigação Científica, pp. 652-655.) and Martínez de Bujanda (1995Martínez de Bujanda, Jesús (dir.) (1995), Index de l’Inquisition Portugaise, 1547, 1551, 1561, 1564, 1581, vol. 4 de Index des Livres Interdis, Sherbooke, Centre d'études de la Renaissance.). Of the eight Indices of prohibited books issued by the Portuguese Inquisition during its existence (1536-1821), seven appeared in the 16th century: 1547, 1551, 1559, 1561, 1564, 1581 and 1597. Cardinal Dom Henrique, the first Portuguese General Inquisitor, enacted the Prohibiçam dos livros defesos, in 1547, a handwritten list which became only known in the early 20th century thanks to António Baião (Dias, 1963Dias, José Sebastião da Silva (1963), "O primeiro rol de livros proibidos", Biblos, 39, pp. 231-327). In 1551 the Rol dos Livros Defesos coordinated by Fr. Jerónimo de Azambuja was published by Germão Galharde. In 1559, the stringent Roman Index of Paul IV was reprinted in Coimbra by João da Barreira at the behest of Bishop D. João Soarez. Another Rol dos Livros Defesos, prepared by Fr. Francisco Foreiro, came out of the press of Johannes Blavio in 1561. Pope Pius IV Index of 1564 was published in Lisbon in Francisco Correa’s workshop some months only after the original: we note that the ten rules of censorship, a kind of “decalogue”, contained in this Roman Index, which came to be Church’s permanent legislation worldwide, were written by a commission where the Portuguese Dominican monk Francisco Foreiro was secretary. The successor of Cardinal D. Henrique, D. Jorge de Almeida, published the seventh Index in 1581 in António Ribeiro’s workshop, which repeated the 1564 rules (Nemésio, 2011Nemésio, Maria Inês (2011), "Índices de livros proibidos no século XVI em Portugal: à procura da ‘Literatura’", Actas do I Encontro do Grupo de Estudos Lusófonos (GEL): Por prisão o infinito: censuras e liberdade na literatura, pp. 1-11.). A new Roman Index, coming out in 1597 at the time of Pope Clement VIII, was printed in Lisbon by Peter Craesbeck at the order of D. António de Matos de Noronha, General Inquisitor and Bishop of Elvas (Nemésio, 2011Nemésio, Maria Inês (2011), "Índices de livros proibidos no século XVI em Portugal: à procura da ‘Literatura’", Actas do I Encontro do Grupo de Estudos Lusófonos (GEL): Por prisão o infinito: censuras e liberdade na literatura, pp. 1-11.). In the 17th and 18th centuries a single Index ruled in Portugal – the Index Auctorum Damnatae Memoriae, an Prohibitory and Expurgatory Index, a major work prepared by the Jesuit Baltazar Álvares and published by Craesbeck in 1624 when the General Inquisitor was D. Fernão Martins de Mascarenhas (Martins, 2011Martins, Maria Teresa Payan (2011), "O Índice Inquisitorial de 1624 à luz de novos documentos", Cultura. Revista de História e Teoria das Ideias, 28, pp. 67-87, Accessible at: https://cultura.revues.org/170 (retrieved on 16/02/2016).).

The ban on the circulation of books in countries of strongly Catholic dominance, as Spain and Portugal, was due primarily to religious concerns. Most authors banned by the Inquisition were humanists or protestants of Northern Europe, such us Erasmus or Luther. In spite of that concentration of the clerical zeal, some of these books had relevant content for the spread or advance of philosophy and science, which were at that time hard to distinguish, and some important scientific books were also targeted by the censor authorities. Henceforth in the 16th and 17th centuries, at a time when modern science was emerging (known today as Scientific Revolution), Southern Europe countries have been less exposed to the torrent of new ideas. The Iberian Peninsula remained at one side of the cultural “iron curtain” which started at that time to divide Europe between North and South. A discussion is still being held whether the Inquisition had a significant influence in the production and import of science in the countries of Southern Europe, hindering their scientific development. Despite the lack of a causal link between the censorship of scientific works and the much discussed “Portuguese decay” after the glorious “time of the Discoveries”, which has been pointed by some authors (Correia and Dias, 2003Correia, Clara Pinto and Dias, João Pedro Sousa (2003), Assim na Terra como no Céu, Ciência, Religião e Estruturação do Pensamento Ocidental, Lisboa, Relógio D’ Água.; Leitão, 2004Leitão, Henrique (2004), "O livro científico antigo, séculos XV e XVI. Notas sobre a situação portuguesa". In: Leitão, Henrique (ed.), O Livro Científico dos Séculos XV e XV. Ciências Físico-Matemáticas na Biblioteca Nacional, Lisboa, Biblioteca Nacional, pp. 15-33.), there is at least a correlation: according to a recent systematic study of scholars in various areas in several places, including Portugal, presented by Anderson (2015Anderson, R. Warren (2015), "Inquisitions and Scholarship", Social Science History, 39 (04), pp. 677-702.), the Inquisition did not favour scientific scholarship in the places it had power, being a factor, mixed with others, which contributed to the referred division. He concluded his study writing: “The Inquisition drastically decreased the number of scholars living in their areas and was a highly exclusive and exploitative institution. Hence, the influence of the Inquisition could have had further reaching effects then just religious.”

In the Iberian Peninsula, Jews or New Christians (Jews forced to conversion) were more affected than humanist or protestant authors. The persecution by the Inquisition of Jews and New Christians, or even of persons they maintained contact with, created a climate of suspicion that hindered the free discussion of ideas, which is a condition for good science. This tension, which lasted in Portugal until the 18th century, chased away from that country some Jewish savants who are nowadays landmarks in the History of Science, being medicine particularly affected. Included in this remarkable group are Amatus, who lived in various places of Europe, are Garcia de Orta (Fontes da Costa and Nobre de Carvalho, 2013Fontes da Costa, Palmira and Nobre de Carvalho, Teresa (2013), "Between East and West: Garcia de Orta’s Colloquies and the Circulation of Medical Knowledge in the Sixteenth Century", Asclepio, 65 (1), https://doi.org/10.3989/asclepio.2013.08.), in Goa in the distant India (the two abandoned Portugal two years before the establishment of Inquisition in the country, a flight which may be seen as a premonition of the years to come), Francisco Sanches, in Toulouse, and Rodrigo de Castro, in Hamburg. One should add that doctors and medicine were under special surveillance since the body was seen as a sacred place.

INQUISITORIAL CENSORSHIP OF THE CENTURIAE Top

The presence of Amatus Lusitanus in the Indices of prohibited books started in the late 16th century. According to the Indices survey done by José Pardo Tomás, Amatus is a censored author in the Indices of 1583, 1584, 1612, 1632, 1640 and 1707, but it does not appear in the 1559 Index (Pardo Tomás, 1991Pardo Tomás, José (1991), Ciencia y Censura: La Inquisición Española y los libros científicos en los siglos XVI y XVII, Madrid, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.). In the 1583 Index the Centuriae was prohibited, but in the 1584 and 1612 ones, they were only expurgated (Pardo Tomás, 1983Pardo Tomás, José (1983), "Obras y autores científicos en los índices inquisitoriales españoles del siglo XVI (1559, 1583 y 1584)", Estudis: Revista de historia moderna, 10, pp. 235-260.), a procedure which continued in later Indices. As a consequence, some copies of the Centuriae were confiscated in some Catholic regions of Spain (Pardo Tomás, 1991Pardo Tomás, José (1991), Ciencia y Censura: La Inquisición Española y los libros científicos en los siglos XVI y XVII, Madrid, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.).

In Portugal, the 1581 Index[9], although interdicting several authors, did not prohibit but only purged Amatus works, allowing therefore for their circulation. This Index states that (Sá, 1983Sá, Artur Moreira de (1983), Índices dos livros proibidos em Portugal no século XVI. Apresentação, estudo introdutório e reprodução fac-similada dos índices, Lisboa, Instituto Nacional de Investigação Científica, pp. 652-655.): “(o)s Amatos Lusitanos também se hão de entregar no sancto Officio, para se riscarem nelles certos passos, que podem fazer damno” (“the Amatus Lusitanus should also be handed out to the Holy Office, to risk some parts which can do harm”).

Amatus is again subject to censorship, now more extensive, in the Index auctorum damnatae memoriae, of 1624[10], which would apply in the country until 1768. This Index includes well-known authors, as German philosopher and theologian Albertus Magnus (ca. 1193-1280, Doctor of the Church since 1931), the Spanish physicians Arnau de Vilanova (1240-ca.1312) and Andrés Laguna (1499-1559), and the German physician and botanist Leonhart Fuchs (1501-1566). A large agreement exists between the Portuguese Index of 1624 and the Spanish Index of 1612. In particular, the text on Amatus is similar in the two Indices (Martins, 2011Martins, Maria Teresa Payan (2011), "O Índice Inquisitorial de 1624 à luz de novos documentos", Cultura. Revista de História e Teoria das Ideias, 28, pp. 67-87, Accessible at: https://cultura.revues.org/170 (retrieved on 16/02/2016).).

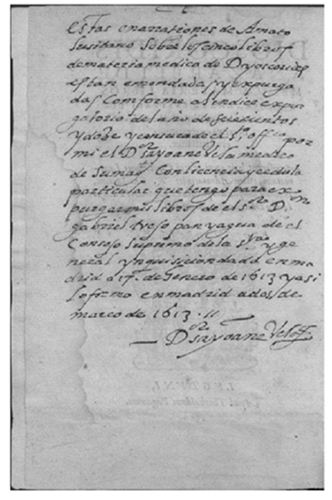

As an example of the censorship exerted on Amatus works, we notice that, in the Coimbra library copy of the important treaty In Dioscorides Anazarbei De medica materia libros quinque, Amatis Lusitani doctoris medici ac philosophi celeberrimi ennarationes eruditissimae[11] (better known as Ennarationes), a reference to censorship appears, as an handwritten note at the turn of the front page, dated from Madrid, March 2, 1613, and signed by D.or Sayoane Veloso (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3. Note on the back of the first page of the book In Anazarbei Dioscorides De materia medica libros quinque ennarrationes... Lugduni: Apud Theobalsum Paganum, 1558 kept at the General Library of the University of Coimbra BGUC Ref. R-40-1

[Descargar tamaño completo]

| |

Baudry had already thrown a first look into Amatus books of the Coimbra University Library, all of them censored, without going into much detail (Baudry, 2012Baudry, Hervé (2012), "A censura dos livros de médicos portugueses. Descrição metodológica dos exemplares conservados nas bibliotecas da Universidade de Coimbra", Cultura. de História e Teoria das Ideias, 30, pp. 275-288.). On the other hand, Costa had examined quickly the Amatus editions existent at the Biblioteca Pública Municipal do Porto, which do not overlap with the Coimbra ones (Costa, 2013Costa, Júlio Manuel Rodrigues (2013), "Arte Médica: breve olhar sobre alguns impressos quinhentistas e seiscentistas da BPMP". In: Andrade, António; Torrão, João; Costa, Jorge and Costa, Júlio (coords.), Humanismo, Diáspora e Ciência, sécs. XVI and XVII, Porto, Universidade de Aveiro e Biblioteca Pública Municipal do Porto.). To undertake a more detailed analysis of the purge of Amatus Centuriae, we examined the Centuriae II-IV (bound together), published in Lyon in 1565[12] and the Centuria VII[13], published in Venice in 1566, both belonging to the General Library of the University of Coimbra, having confronted them with the Centuriae I to IV (bound together) published in Venice in 1557[14] and the Centuria VII published in Lyon, 1570[15], apparently not censored, which are available online from Spanish historical libraries. It was useful to use, as reference, a modern Portuguese translation of the 1620 Bordeaux edition of the Centuriae (Amato Lusitano, 2010 Amato Lusitano, (2010), Centúrias de Curas Medicinais. Translated into Portuguese by Firmino Crespo, Lisboa, Centro Editor Livreiro da Ordem dos Médicos.). We noticed that several excerpts have been purged in the Coimbra copies. While we cannot say with absolute certainty that these cuts were done by inquisitors, their look, the nature of scratched themes and the publication dates point to this conclusion. This evidence is reinforced by the appearance, in a handwritten note, on the back of the first page of some editions, that the work has been censored, giving the name of the censor and the date of censorship. In the Lyon 1565 edition existent in Coimbra, one knows through a note of this type that it was censored in 1612, no mention being made to the censor name. We believe that this censorship was done by hand only in a few copies, certainly following general guidelines. The censor’s “pencil” was iron gall ink. When it was too concentrated it could even burn the paper; when less concentrated, the censored phrases would be legible. In two copies of the Centuriae II-IV of the Lyon edition of 1565, one inspected at the Coimbra library and the other online at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid[16], we found that the black ink and style of “blur” used were similar in the covered excerpts.

The censored phrases refer mainly to affections of human reproduction (sexuality and gynaecology), the remaining being related to religious subjects, indicating that the censor had theological formation. We illustrate this statement with some examples of the purges made in the above-mentioned Coimbra copies of the Centuriae.

A case which refers to sexuality is portrayed in Curatio XVIII of Centuria II. In this Curatio, referring to “an individual [a Jew] who could not perform the sexual act”, part of the prescription indicated by Amatus is erased. We give the omitted text (our translation):

“We admit as certain that fish, being eaten hot and well cooked, although protected by scales or covered by a shell, excite the libido. But it is preferable to pass over in silence those who were forbidden by religion” [17].

Below the drug names used for sexual arousal were deleted. They were considered inconvenient by the officials of a Church which advocated that the sexual organs were not intended for pleasure, but only procreation. In case of illness, they should only be restored to accomplish the correct purpose (Rodrigues, 2005Rodrigues, Isilda (2005), Amato Lusitano e as problemáticas sexuais – Algumas considerações para uma nova perspectiva de análise das Centúrias de Curas Medicinais, Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Ph.D. thesis.).

In the same Centuria II, there are, in Curatio XXXIX, some comments on “A young girl who became a man,” with crossed parts, which we quote (our translation):

“When the age arrives when women usually have their first menstruation, instead of this, it started to appear to her and to develop a penis that until that time had been occulted in the interior. Thus she transitioned from female to male, dressed manly and was baptized with the name of Manuel”[18].

This is a cure in which, again, the issue is sexuality, more precisely transsexuality, a dark zone which, at the time, still did not even have a name. The absence of the term indicates the absence of the concept: some events were not supposed to take place at all. Some recent research works are very pertinent on this issue (DeVun, 2008DeVun, Leah (2008), "The Jesus Hermaphrodite: Science and Sex Difference in Premodern Europe", Journal of the History of Ideas, 69 (2), pp. 193-218. and 2015DeVun, Leah (2015), "Erecting Sex: hermaphrodites and the Medieval Science of Surgery", Osiris, 30, pp. 17-37.; Soyer, 2012Soyer, François (2012), Ambiguous Gender in Early Modern Spain and Portugal: Inquisitors, Doctors and the Transgression of Gender Norms, Leiden, Brill.; Cleminson, and Vázquez García, 2013Cleminson, Richard and Vázquez García, Francisco (2013), Sex, Identity and Hermaphrodites in Iberia, 1500-1800, London, Pickering and Chatto.).

In Curatio XLVII of the Centuria II, entitled “From an individual who, tormented by dysentery, made intercourse with a woman and recovered,” Amatus comments were totally erased. Their content is the following (our translation):

“Hippocrates said in the last pages of the books Morbis Vulgaribus that dysentery cures with lascivious life. The frequency of brothels is, as he says, an awkward licentiousness, which the cynic Diogenes used when he expected the harlot. Since she had arrived later to him who was expecting her, he presented to her shamelessly and against the commandment of God. The hand had anticipated the celebration of copulation. He had launched the semen on the ground after manipulating the pudenda. On the continence and constancy of this man one should read Galen, in his book 6 De Locis Affectis, chapter IV. In fact, this one like the other is worthy of censure in this matter”[19].

These comments refer to masturbation, an act which was considered at the time a mortal sin, with very precise penitential prescriptions. This was certainly not a topic on which the religious authorities were willing to let a doctor freely transcribe the classics, especially in a book intended for a wide readership (Correia, 1998Correia, Clara Pinto (1998), Ovário de Eva, Lisboa, Relógio D’ Água.).

Dov Front called attention to another interesting case of censorship in the Centuria IV, this one published in Lyon in 1580 (Front, 2001Front, Dov (2001), "The expurgation of medical books in sixteenth-century Spain", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 75 (2), pp. 290-296.). Indeed, in Curatio XXXVI, Centuria IV, entitled “On the spring in the matrix”, Amatus reports the pregnancy of a nun, discussing the possibility of “virginal conception”. According to Front, that case would have been expurgated by the Inquisition, by the hand of Friar Gaspar de Uzeda, in 1586 (Front, 2001Front, Dov (2001), "The expurgation of medical books in sixteenth-century Spain", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 75 (2), pp. 290-296.). Amatus, in his comments, based on Averroes and a rabbinic source (Alphabet of Bem Sira), admits that cases like that could occur naturally.

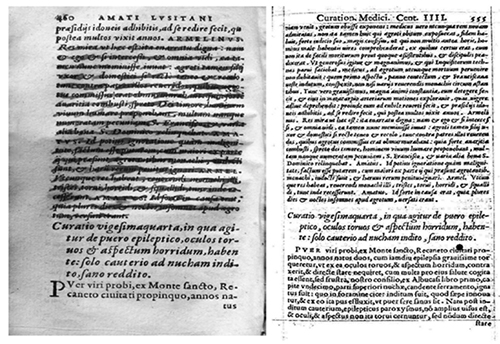

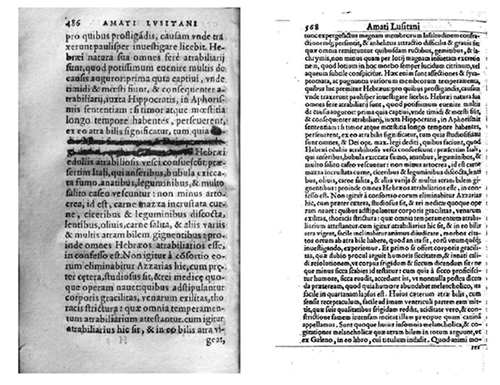

In the above-mentioned edition, the censor erased completely Curatio XXXVI with black ink, but the respective title was left intact in the final contents list (Front, 2001Front, Dov (2001), "The expurgation of medical books in sixteenth-century Spain", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 75 (2), pp. 290-296.). In the Centuria IV we have examined, published earlier in Lyon, in 1565, belonging to the University of Coimbra collections, that Curatio was also completely expurgated. We present in Figure 4 the corresponding images, which, in the original version, takes up 56 lines spread over three pages. Interesting enough, the text could still be read in spite of the censor efforts. Comparing the two Lyon editions (1565 and 1580) we noticed that Curatio XXXVI was excluded with a very similar scribbled style.

In the 1620 Bordeaux version[20], this Curatio, entitled “On a spring in the matrix”, only comprises 17 sentences. The mention to Averroes appears, but not to the rabbinic source. There are no extended comments and the dubious pregnancy in question is not assigned to a “nun” but to a “girl”, followed by a short remark of the author stating that one should not talk about the case. Probably the Inquisition had ordered to replace “nun” by “girl”. This amputation should not have come from Amatus, but from the hand of a censor. We translate the relevant text of the 1620 edition:

“A certain girl, feeling ill, said she had the impression of something moving inside her body. Therefore, some women claimed that she had a spring in her belly. I did not doubt that this could happen. In fact we know from what Galen says in book 14 of De Usu Partium, that a spring or something similar cannot be generated without intercourse with a man, saying: “No one ever saw a woman conceive a spring or anything else without a man”. So I advised them either to conceal the case or to say that it was another kind of disease. Averroes, in his book Colectorio, asserts that a woman can get pregnant from male semen left in the bath.”[21]

The censorship of sentences of religious nature was also is a practice of the Inquisition when the author deviated from orthodoxy. The same happens in the comments of Curatio XXIII, of Centuria IV, where some comments were scratched. They say the following (our translation):

“Armelinus – It is an extraordinary and worthy event to be told. However, since I have this present and seen it all, would not now be able to solve it. If I remember correctly and reconstituted, the children of the patient, his wife and the servants murmured against the reverend fathers, whom he had trusted, because, perhaps excited by greed, contempt of fear of God, they intended to bury a man alive since he made lots of money to St. Francis and various other goods to St. Dominic.

Amatus - In my opinion this could have happened more by ignorance than malice since the majority of the brothers attending the sick uneducated and deeply ignorant of this matter.

Armelinus - In any case, it is certain that the friar reverends withdrew sad, threatening and haunted.

Amatus - This should be the case because they had remained several days and nights without sleep, around the patient.”[22]

It would be inadequate to be known that a priest wished the death of someone so that the Church could receive a large fortune (Figure 5).

|

Figure 5. Excerpt of Curatio XXIII, Centuria IV Lugduni, 1565, p. 460 and excerpt of Curatio XXIII, Centuria IV, Venitii, 1557, p. 555

[Descargar tamaño completo]

| |

Another example is the text excerpt expunged in Curatio XLII, Centuria IV, which says referring to the Jews: “Then, since they all are very zealous and devoted to God’s law” (Figure 6). In this case, to aggravate the issue, Jewish customs were the bête noire of the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions.

|

Figure 6. Excerpt of Curatio XLII, Centuria IV, Lugduni, 1565, p. 486, and excerpt of Curatio XLII, Centuria IV, Venitii, 1557, p. 568

[Descargar tamaño completo]

| |

Finally, it should be added that, in Centuria VII[23], the famous Amatus oath was also victim of censorship (Figure 7). The original oath (Amati jusjurandum), written in Thessalonica in 1559, first appeared as an afterword of Centuria VII, 1561, the last one. However, in the Bordeaux 1620 edition parts of the oath were omitted, including the reference to Moses and the Ten Commandments. The first translation into Portuguese was made by Alberto da Rocha Brito in 1937Brito, A. da Rocha (1937), "Juramento de Amato Lusitano", Coimbra Médica, Ano IV (Jan 1937, 1), pp. 33-38. (Brito, 1937Brito, A. da Rocha (1937), "Juramento de Amato Lusitano", Coimbra Médica, Ano IV (Jan 1937, 1), pp. 33-38.), respecting the original and not the truncated 1620 edition (Rasteiro, 2005Rasteiro, Alfredo (2005), "Amato Lusitano (1511-1568. Tensões e diferenças na Europa do século XVI", Medicina na Beira Interior. Da Pré-História ao Século XXI, Cadernos de Cultura, XIX, pp. 6-16.).

We transcribe an excerpt of this notable Amatus oath (our translation):

“I swear before immortal God and by his ten most holy commandments, given on Mount Sinai to the Jewish People, through Moses, after the captivity in Egypt, that in my clinic I never had more to my heart than promoting that the faith intact of things would come to the knowledge of the comers. (...) Always in everything I required the truth; if I am forsworn, let fall upon me the wrath of the Lord and his minister Raphael and let no one never have confidence in the exercise of my art. (...) Often I firmly rejected big salaries, always having more in view that the sick regain health by my intervention than I become richer for their generosity or their money; treating patients, I never cared to know whether they were Jews, Christians, or followers of the Mohammedan Law; I never run after honours and glories and with equal care I treated poor and born in nobility; I never teased the disease; in prognoses I always said what I felt; I never favoured a pharmacist more than another, unless when at some I recognized, perhaps, more skill in the art and more kindness in the heart, and due to that I preferred him to the others (...) In short, I never did anything that could embarrass an illustrious and egregious physician”.

CONCLUSIONS Top

The works of the Portuguese physician Amatus Lusitanus have been studied by several researchers from all around the world. Analysing the censorship exerted on Amatus main work, Curatiorum Medicinalium centuriae, we noticed that his name appears, from late 16th century onwards, in the Church Indices: it appears in the Spanish Indices from 1583 to 1707, first in a prohibitory Index and afterwards in expurgatory ones, and in the Portuguese Indices of 1581 and 1624, the first prohibitory but with some general expurge indications and the second both prohibitory and expurgatory. Except for the first appearance in the Spanish Indices, Amatus is as an author whose works just needed to be expunged following general instructions inscribed in the Roman Indices which appeared after the Council of Trent.

Based on our comparison of the Centuriae II-IV published in Lyon in 1565, and the Centuria IV, published in Venice in 1566, and not expurgated editions of the same books, we conclude that the censored sentences refer primarily to the affections belonging to the areas of sexuality, gynaecology and obstetrics but also to some topics of strictly religious nature. The way the texts are purged, regarding colour and scrabble style, indicates that the censorship was made by the Inquisition. Censored editions were different probably depending on the different censor. There was an evolution in the censorship content and style. For example, while Curatio XXXVI was totally expunged in the Lyon editions of 1565 and 1580, in the Bordeaux edition of 1620 the comments appear are short, after an intermediate revision: in the 1580 edition a pregnancy of a nun is extensively discussed, but the nun is replaced by a girl, this only being discussed shortly, in the 1620 edition. We have here clearly a censored edition instead of censored copies as in the previous editions we have examined.

In the present work, after an overview of inquisitorial censorship, in special of medical books, we essayed a microanalysis of some of the Amatus works available at the General Library of the University of Coimbra. Although the inquisitorial censorship, which lasted for centuries, certainly affected science and society, as it is generally recognized, a broader view is needed for quantitative and qualitative views of its action. Much work remains to be done on the modus operandi and, mainly, the effect of censorship in the scientific and cultural development of the Catholic nations where the Inquisition was operating.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSTop

We would like to thank the General Library of the University of Coimbra for providing the figures.

NOTES Top

|

| [1] | Johann Bauhino and Johann Henricus Cherlero, Historia plantarum universalis, nova, et absolutissima cum consensu et dissensu circa eas, Ebroduni [Yverdon], 3 vols., 1650-1651, General Library of the Univerity of Coimbra – BGUC Ref. 2-23-12-1. This is considered one of the major books on botanics of the 16th century. The first author is contemporaneous of Amatus, but the book is posthumous to both authors. |

| [2] | Andreae Vesalii, De humani corporis fabrica, Johannes Oporinus, Basileae [Basel], 1543. BGUC Ref. 4 A-21-14-1. |

| [3] | Caderno de Cultura. Medicina na Beira Interior (2012), XXVI, pp. 1-165. Accessible in: http://www.historiadamedicina.ubi.pt/cadernos_medicina/vol26.pdf, (retrieved on 18/10/2016) |

| [4] | Amato Lvsitani, Curationum medicinalium centuriae septem, varia multiplicique rerum cognitione referte, Burdigalae [Bordeaux], 1620. BGUC Refs. 2-18-7-65 and 4 A-27-20-20 c.2 . A similar edition is available on-line, accessible at Universidad Complutense de Madrid: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=ucm.5327378028;view=1up;seq=24 (retrieved on 05/04/2016) The first complete edition of the Centuriae came out in Lyon in 1580. Written in Latin, there is a Portuguese translation by Firmino Crespo, first published in 1983 by the Faculty of Medical Sciences, New University of Lisbon, and republished in Lisbon in 2010 in two volumes by the Portuguese Medical Association (Amato Lusitano, 2010 Amato Lusitano, (2010), Centúrias de Curas Medicinais. Translated into Portuguese by Firmino Crespo, Lisboa, Centro Editor Livreiro da Ordem dos Médicos.). |

| [5] | Amato Lusitano. Curationum medicinalium, centuriae duae tertia et quarta. Cum indice omnium curationum & rerum memorabilium quae ipsis centurijs continentur. Lugduni [Lyon]: apud Gulielmum Rouillium, sub scuto Veneto, 1565. BGUC Ref. 2-4-1-21. |

| [6] | Amato Lusitano. Curationum medicinalium Amati Lusitani... Centuria septima Thessalonice curationes habitas continens, varia multiplicique doctrina referta. Venetiis [Venice]: apud Vincentium Valgrisium, 1566. BGUC Ref. 2-4-1-20. |

| [7] | See note 4. |

| [8] | Amato Lusitano, Curationum medicinalium centuria prima, multiplici variaque rerum cognitione referta. Praefixa est eiusdem auctoris commentatio in qua docetur quomodo se medicus habere debeat in introitu ad aegrotantem, simulque de crisi, & diebus decretoriis, iis qui artem medicam exercent, & quotidie prosalute agrotorum in collegium descendunt longè utilíssima, Florentiae [Florence], [Ex]cudebat Laurentius Torrrentinus. 1551, BGUC Ref. 4-7-41-29. |

| [9] | Antonio Ribeiro, Catalogo dos livros qve se prohibem nestes regnos & senhorios de Portugal, por mandado do illustrissimo & reuerendissimo senhor Dom Iorge Dalmeida Metropolytano Arcebispo de Lisboa, Inquisidor geral, &c., Lisboa [Lisbon]: A. Ribeiro, 1581. Reproduced in Sá, 1983Sá, Artur Moreira de (1983), Índices dos livros proibidos em Portugal no século XVI. Apresentação, estudo introdutório e reprodução fac-similada dos índices, Lisboa, Instituto Nacional de Investigação Científica, pp. 652-655., pp. 652-655. |

| [10] | Índex Auctorum damnatae memoriae, tu metiam librorum, qui uel simpliciter uel ad expurgationem usque prohibentur, ueldenique iam expurgati permittuntur, editus auctoritate Illmi Domini D. Fernandi Martins Mascaregnas, Algarbiorum Episcopi, regii status Consiliarii ac Regnorum Lusitaniae Inquisitoris Generalis, Lisboa [Lisbon]: Pedro Craesbeck, 1624. BGUC: 4 A-21-7-16 c.2 and six other copies. |

| [11] | Amatus Lusitanus, In Dioscorides Anazarbei De medica materia libros quinque, Amatis Lusitani doctoris medici ac philosophi celeberrimi ennarationes eruditissimae, Lugduni [Lyon]: apud Theobaldum Paganum, 1558. BGUC R-40-15 Accessible at: http://goo.gl/mPKiBu (retrieved on 16/02/2016). |

| [12] | See note 5. |

| [13] | See note 6. |

| [14] | Amatus Lusitanus. Curationum medicinalium Amati Lusitani medici physici praestantissimi centuriae quatuor: quibus praemittitur Commentatio de introitu medici ad aegrotantem, de crisi & diebus decretorij.... Venetiis [Venice]: apud Balthesarem Constantinum, sub diui Georgij signo, 1557. There are 12 works of Amatus Lusitanus online at the Virtual Library Miguel de Cervantes, at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, accessible at http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/buscador/?q=centuriae (retrieved on 16/02/2016). |

| [15] | Amatus Lusitanus, Curationum medicinalium centuria septima: Thessalonicae curationes habitas continens...: accessit index... Lugduni [Lyon]: apud Gulielmum Rouillium, 1570. Accessible at: http://data.cervantesvirtual.com/manifestation/276169, (retrieved on 16/02/2016). |

| [16] | Accessible at: http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/amati-lusitani-curationum-medicinalium-centuriae-duae-tertia-et-quarta-cum-indice-omnium-curationum/ (retrieved on 05/04/2016). |

| [17] | Curatio XVIII, Centuria II, Venitiis [Venice], 1557, p. 201. |

| [18] | Curatio XXXIX, Centuria II, Venitiis [Venice], 1557, pp. 274-275. |

| [19] | Curatio XLVII, Centuria II, Venitiis [Venice], 1557, p. 289. |

| [20] | See note 4. |

| [21] | Curatio XXXVI, Centuria IV, Burdigalae [Bordeaux], 1620. |

| [22] | Curatio XXIII, Centuria IV, Venitii [Venice], 1557, p. 555. |

| [23] | See note 6. |

|

BIBLIOGRAPHYTop

|

| ○ | Altbauer-Rudnik, Michal (2009), Prescribing Love: Italian Jewish physicians writing on lovesickness in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Jerusalem, European Forum at the Hebrew University. |

| ○ | Amato Lusitano, (2010), Centúrias de Curas Medicinais. Translated into Portuguese by Firmino Crespo, Lisboa, Centro Editor Livreiro da Ordem dos Médicos. |

| ○ | Anderson, R. Warren (2015), "Inquisitions and Scholarship", Social Science History, 39 (04), pp. 677-702. |

| ○ | Andrade, António Manuel Lopes (2010), "Ciência, negócio e religião: Amato Lusitano em Antuérpia". In: Castro, Inês de Ornellas and Anastácio, Vanda (coords.), Revisitar os Saberes, Referências Clássicas na cultura portuguesa do Renascimento à época moderna, Lisboa, Centro de Estudos Clássicos, pp. 9-50. |

| ○ | Andrade, António Manuel Lopes (2012), "Os inventários dos bens de Amato Lusitano, Francisco Barbosa e Joseph Molcho, em Ancona, na fuga à Inquisição (1555)", Ágora. Estudos Clássicos em debate, 14.1, pp. 45-90, Accessible at: http://revistas.ua.pt/index.php/agora/article/view/2268 (retrieved on 08/01/2015). |

| ○ | Andrade, António; Torrão, João; Costa, Jorge and Costa, Júlio (coords.), (2013), Humanismo, Diáspora e Ciência, séculos XVI e XVII, Porto, Universidade de Aveiro e Biblioteca Pública Municipal do Porto, https://doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-0945-4. |

| ○ | Andrade, António; Mora, Carlos and Torrão, João (eds.), (2015), Humanismo e Ciência, Antiguidade e Renascimento, Aveiro, Universidade de Aveiro Editora e Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, pp. 513-541, [online], https://doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-0941-6. |

| ○ | Bacic, Jurica; Vilovic, Katarina and Baronica, Koraljka Bacic (2002), "The gynaecological-obstetrical practice of the renaissance physician Amatus Lusitanus (Dubrovnik, 1555-1557)", European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 104 (2), pp. 180-185. |

| ○ | Baldini, Ugo and Spruit, Leen (eds.), (2009), Catholic Church and Modern Science. Documents from the Archives of the Roman Congregations of the Holy Office and the Index, Roma, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, [Fontes Archivi Sancti Officii Romani]. |

| ○ | Baudry, Hervé (2012), "A censura dos livros de médicos portugueses. Descrição metodológica dos exemplares conservados nas bibliotecas da Universidade de Coimbra", Cultura. de História e Teoria das Ideias, 30, pp. 275-288. |

| ○ | Bethencourt, Francisco (1994), História das Inquisições: Portugal, Espanha e Itália, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores. |

| ○ | Brito, A. da Rocha (1937), "Juramento de Amato Lusitano", Coimbra Médica, Ano IV (Jan 1937, 1), pp. 33-38. |

| ○ | Capparoni, Pietro (1941), "Amato Lusitano e la sua testimonianza della scoperta delle valvole delle vene fatta da G. B. Canano", Atti e Memorie dell’Accademia di Storia dell’Arte Sanitaria, appendice alla Rassegna di Clinica, Terapia e Scienze affini, Anno XL (Fasc. 4), Luglio-Agosto. |

| ○ | Class, Monika (2014), "Introduction Medical Case Histories as Genre; New Approaches", Literature and Medicine, 32 (1), pp. VII-XVI. |

| ○ | Cleminson, Richard and Vázquez García, Francisco (2013), Sex, Identity and Hermaphrodites in Iberia, 1500-1800, London, Pickering and Chatto. |

| ○ | Correia, Clara Pinto (1998), Ovário de Eva, Lisboa, Relógio D’ Água. |

| ○ | Correia, Clara Pinto and Dias, João Pedro Sousa (2003), Assim na Terra como no Céu, Ciência, Religião e Estruturação do Pensamento Ocidental, Lisboa, Relógio D’ Água. |

| ○ | Costa, Júlio Manuel Rodrigues (2013), "Arte Médica: breve olhar sobre alguns impressos quinhentistas e seiscentistas da BPMP". In: Andrade, António; Torrão, João; Costa, Jorge and Costa, Júlio (coords.), Humanismo, Diáspora e Ciência, sécs. XVI and XVII, Porto, Universidade de Aveiro e Biblioteca Pública Municipal do Porto. |

| ○ | DeVun, Leah (2008), "The Jesus Hermaphrodite: Science and Sex Difference in Premodern Europe", Journal of the History of Ideas, 69 (2), pp. 193-218. |

| ○ | DeVun, Leah (2015), "Erecting Sex: hermaphrodites and the Medieval Science of Surgery", Osiris, 30, pp. 17-37. |

| ○ | Dias, José Sebastião da Silva (1963), "O primeiro rol de livros proibidos", Biblos, 39, pp. 231-327. |

| ○ | Dürrigl, Marija-Ana and Fatovic-Ferencic, Stella (2002), "The medical practice of Amatus Lusitanus in Dubrovnik (1556-1558) a short reminder on the 445th anniversary of his arrival", Acta Médica Portuguesa, 15, pp. 37-40. |

| ○ | Fontes da Costa, Palmira and Nobre de Carvalho, Teresa (2013), "Between East and West: Garcia de Orta’s Colloquies and the Circulation of Medical Knowledge in the Sixteenth Century", Asclepio, 65 (1), https://doi.org/10.3989/asclepio.2013.08. |

| ○ | Friedenwald, Harry (1937), "Amatus Lusitanus", Bulletin of the Institute of History of Medicine, 5, pp. 603-653. |

| ○ | Friedenwald, Harry (1955), "Medical works of Amatus Lusitanus". In: Homenagem ao Doutor João Rodrigues de Castelo Branco (Amato Lusitano), Castelo Branco, Câmara Municipal, pp. 177-191. |

| ○ | Front, Dov (1998), "The Expurgation of the Books of Amatus Lusitanus", Book Collectors, 47, pp. 20-36. |

| ○ | Front, Dov (2001), "The expurgation of medical books in sixteenth-century Spain", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 75 (2), pp. 290-296. |

| ○ | Glesinger, Lavoslav (1968), "Amato Lusitano em Ragusa", Estudos de Castelo Branco, 28, pp. 158-178. |

| ○ | Guerra, Francisco (1989), Historia de la medicina, 1, Madrid, Ediciones Norma, S.A., pp. 294-310. |

| ○ | Guimarães Pinto, Antônio (2013), "Preconceito e cultura: o ataque de Peitro Andrea Mattioli a Amato Lusitano", Humanitas, 65, pp. 161-186. |

| ○ | Laín Entralgo, Pedro (1989), Historia de la medicina, Barcelona, Salvat. |

| ○ | Leibowitz, Joshua Otto (1953), "A probable case of peptic ulcer described by Amatus Lusitanus", Bulletin of the History of Medicines, 27, pp. 212-216. |

| ○ | Leibowitz, Joshua Otto (1958), "Amatus Lusitanus and the Obturator in Cleft Palates", Journal of the History of Medicine, 13, pp. 492-503. |

| ○ | Leibowitz, Joshua Otto (1968), "Amatus Lusitanus (1511-1568) à Salonique", Estudos de Castelo Branco, 28, pp. 90-93. |

| ○ | Leitão, Henrique (2004), "O livro científico antigo, séculos XV e XVI. Notas sobre a situação portuguesa". In: Leitão, Henrique (ed.), O Livro Científico dos Séculos XV e XV. Ciências Físico-Matemáticas na Biblioteca Nacional, Lisboa, Biblioteca Nacional, pp. 15-33. |

| ○ | López Terrada, María Luz and Salavert Fabiani, Vicente L. (1999), "Le médecin de la Renaissance à l’aube des Lumières". In: Callabert, Louis (dir.), Histoire du médecin, Paris, Flammarion, pp. 143-150. |

| ○ | Marcocci, Giuseppe and Paiva, José Pedro (2013), História da Inquisição Portuguesa — 1536-1821, Lisboa, Esfera dos Livros. |

| ○ | Martins, Maria Teresa Payan (2011), "O Índice Inquisitorial de 1624 à luz de novos documentos", Cultura. Revista de História e Teoria das Ideias, 28, pp. 67-87, Accessible at: https://cultura.revues.org/170 (retrieved on 16/02/2016). |

| ○ | Martínez de Bujanda, Jesús (dir.) (1995), Index de l’Inquisition Portugaise, 1547, 1551, 1561, 1564, 1581, vol. 4 de Index des Livres Interdis, Sherbooke, Centre d'études de la Renaissance. |

| ○ | Martínez de Bujanda, Jesús (2016), El Índice de libros prohibidos y expurgados de la Inquisición española (1551-1819), Madrid, Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos. |

| ○ | Morais, João Augusto David de (2011), Eu, Amato Lusitano. No V Centenário do seu Nascimento, Lisboa, Edições Colibri. |

| ○ | Néhama, J. (1955), "Amato Lusitano à Salonique". In: Homenagem ao Doutor João Rodrigues de Castelo Branco (Amato Lusitano), Castelo Branco, Câmara Municipal, pp. 213-214. |

| ○ | Nemésio, Maria Inês (2011), "Índices de livros proibidos no século XVI em Portugal: à procura da ‘Literatura’", Actas do I Encontro do Grupo de Estudos Lusófonos (GEL): Por prisão o infinito: censuras e liberdade na literatura, pp. 1-11. |

| ○ | Papaspyros, Nick Spyros (1964), The history of diabetes mellitus (2nd. ed.), Stuttgart, Georg Thieme. |

| ○ | Pardo Tomás, José (1983), "Obras y autores científicos en los índices inquisitoriales españoles del siglo XVI (1559, 1583 y 1584)", Estudis: Revista de historia moderna, 10, pp. 235-260. |

| ○ | Pardo Tomás, José (1991), Ciencia y Censura: La Inquisición Española y los libros científicos en los siglos XVI y XVII, Madrid, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. |

| ○ | Pereira, Isaías da Rosa (1976), Notas históricas acerca de índices de livros proibidos e bibliografia sobre a Inquisição, Lisboa, Livraria Editora. |

| ○ | Pérez Alencart, Alfredo (2005), "Descubrimiento de Amato Lusitano", Medicina na Beira Interior. Da Pré-História ao Século XXI — Cadernos de Cultura, 19, pp. 40-41. |

| ○ | Peset Reig, Mariano and Peset Reig, José Luis (1968), "El aislamiento científico español a través de los índices del inquisidor Gaspar de Quiroga de 1583 y 1584", Anthologica Annua, XVI, pp. 25-41. |

| ○ | Pita, João Rui and Pereira, Leonor (2015), "Estudos contemporâneos sobre Amato Lusitano". In: Andrade, António; Mora, Carlos and Torrão, João (coords.), Humanismo e Ciência, Antiguidade e Renascimento, Aveiro, Universidade de Aveiro Editora, pp. 513-541. |

| ○ | Pomata, Gianna (2010), "Sharing Cases: the Observationes in Early Modern Medicine", Early Science and Medicine, 15 (3), pp. 193-236. |

| ○ | Rasteiro, Alfredo (2005), "Amato Lusitano (1511-1568. Tensões e diferenças na Europa do século XVI", Medicina na Beira Interior. Da Pré-História ao Século XXI, Cadernos de Cultura, XIX, pp. 6-16. |

| ○ | Rego, Raul (1982), Os índices expurgatórios e a cultura portuguesa, Lisboa, Instituto de Cultura e Língua Portuguesa. |

| ○ | Rodrigues, Isilda (2005), Amato Lusitano e as problemáticas sexuais – Algumas considerações para uma nova perspectiva de análise das Centúrias de Curas Medicinais, Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Ph.D. thesis. |

| ○ | Rodrigues, Isilda and Fiolhais, Carlos (2013), "O ensino da medicina na Universidade de Coimbra no século XVI", História, Ciência e Saúde – Manguinhos, 20 (2), pp. 435-456. |

| ○ | Rodrigues, Isilda and Fiolhais, Carlos (2015), "Amato Lusitano na cultura científica do seu tempo – Cruzamentos com Vesálio e Orta", Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de História da Ciência, 8 (1), pp. 79-88, Accessible at: https://estudogeral.sib.uc.pt/bitstream/10316/40734/1/Isilda%20Rodrigues_Carlos%20Fiolhais.pdf (retrieved on 04/10/2016). |

| ○ | Rudy, Hirsch (1931), "Amatus Lusitanus", Archeion, 13, pp. 424-449. |

| ○ | Rudy, Hirsch (1955), Homenagem ao Doutor João Rodrigues de Castelo Branco (Amato Lusitano), Castelo Branco, Câmara Municipal, pp. 193-211. |

| ○ | Sá, Artur Moreira de (1983), Índices dos livros proibidos em Portugal no século XVI. Apresentação, estudo introdutório e reprodução fac-similada dos índices, Lisboa, Instituto Nacional de Investigação Científica, pp. 652-655. |

| ○ | Salomon, Max (1901), Amatus Lusitanus und seine Zeit. Ein Beitrag sur Geschichte der Medizin im 16. Jahrhundert, Sonderabdruck der Zeitschrift für Klinische Medizin, vols. 41-42, Berlin, reimp. Nabu Press, 2010. Accessible at: https://archive.org/details/b2900813x (retrieved on 18/10/2016). |

| ○ | Samoggia, Luigi (1966), "Aspetti del pensiero scientifico di Amato Lusitano", Pagine di Storia della Medicina, 10 (3), pp. 14-23. |

| ○ | Santos Filho, Lycurgo de Castro (1991), História Geral da Medicina Brasileira, vol. 1, São Paulo, HUCITEC Editora. |

| ○ | Seide, Jacob (1955), "The two diabetics of Amatus Lusitanus", Imprensa Médica, 19 (11), pp. 670-674. |

| ○ | Solberg, Michael (2013), "Empiricism in sixteenth-century medical practice: the Notebooks of Georg Handsch", Early Science and Medicine, 18 (6), pp. 487-516. |

| ○ | Soyer, François (2012), Ambiguous Gender in Early Modern Spain and Portugal: Inquisitors, Doctors and the Transgression of Gender Norms, Leiden, Brill. |

| ○ | Tarrant, Neil (2014), "Censoring Science in sixteenth- century Italy: recent (and not-so-recent research)", History of Science, 52 (1), pp. 1-24. |

| ○ | Tartalja, Hrvoje (1985), "Les médicaments qu’Amatus Lusitanus utilisait à l’occasion de son travail à Dubrovnik". In: Puerto Sarmiento, Francisco Javier, Farmacia e industrializacion. Homenaje al doctor Guillermo Folch Jou, Madrid, Sociedad Española de Historia de la Farmacia, pp. 237-246. |

|