ESTUDIOS / RESEARCH STUDIES

SHARING ARCHITECTURAL MODELS: MORPHOLOGIES AND SURVEILLANCE FROM THE SEVENTEENTH TO THE NINETEENTH CENTURIES

Pedro Fraile

Departamento de Geografía y Sociología, Universitat de Lleida

Email: p.fraile@geosoc.udl.cat

ORCID iD: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0117-1042

Quim Bonastra

Departamento de Geografía y Sociología, Universitat de Lleida

Email: quim.bonastra@geosoc.udl.cat

ORCID iD: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4717-8450

ABSTRACT

Spatial and territorial organization is an important factor in the configuration of control and surveillance strategies at work in our society. Architecture in general and certain buildings in particular have been key devices in exercising said control and surveillance.

In these pages we look at the building structures in facilities specially designed for the control and custody of their occupants. We begin with the Casas de Misericordia, which appeared in the 16th century and were designed to house marginalized people mostly from urban environments, and go over the morphologies of prisons, hospitals, and quarantine stations.

We analyze the transfer of building structures from one kind of establishment to another, and discuss how their specific functions progressively fixed their morphologies.

Finally, we focus on the discourse built in Spain, from its origins in the 16th century until its realizations in the first half of the 19th century, when a marked institutional specialization took place and building structures became more stable, dealing with theoretical proposals as well as what was done in the practice.

COMPARTIENDO MODELOS ARQUITECTÓNICOS: MORFOLOGÍAS Y VIGILANCIAS DEL SIGLO XVII AL XIX

RESUMEN

La organización espacial y territorial es un factor importante en la configuración de las estrategias de control y vigilancia que funcionan en nuestra sociedad. La arquitectura en general, y determinados edificios en particular, han sido dispositivos importantes para el desempeño de tales tareas.

En estas páginas se estudian las estructuras constructivas de establecimientos especialmente diseñados para el control y la custodia de sus habitantes, comenzando por las “Casas de Misericordia” diseñadas para recoger a los marginados, principalmente urbanos, desde el siglo XVI, y se rastrean las morfologías de cárceles, hospitales y lazaretos.

Analizamos la transferencia de estructuras constructivas de un establecimiento a otro y cómo la reflexión sobre las funciones específicas de cada uno de ellos fue fijando sus morfologías.

Finalmente, se presta atención al discurso construido en España, desde sus orígenes en el siglo XVI hasta sus concreciones en el XIX, ocupándonos tanto de las propuestas teóricas como de las realizaciones.

Received: 07-03-2016; Accepted: 03-10-2016.

Cómo citar este artículo/Citation: Fraile, Pedro and Bonastra, Quim (2017), "Sharing architectural models: morphologies and surveillance from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries", Asclepio, 69 (1): p170. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/asclepio.2017.02

KEYWORDS: Hospitals; Prisons; Quarantine Stations; Liquid Surveillance; Solid Surveillance; Coercive Surveillance; Inquisitive Surveillance.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Hospitales; Cárceles; Lazaretos; Vigilancia líquida; Vigilancia sólida; Vigilancia inquisitiva; Vigilancia coercitiva.

Copyright: © 2017 CSIC. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) Spain 3.0.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION Top

Safety and surveillance are deeply-rooted concepts in contemporary society, and they are currently gaining relevance as a consequence of the social and economic changes we are experiencing. The beginning of the 21st century was marked by the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York, and following them, a succession of wars and confrontations in a complex and globalized world. This threat, resulting from unresolved conflicts originating far away, has reached the heart of what is called the First World.

All of this places surveillance among the main social issues, while stories of espionage on high-ranking politicians make the news, and concern over the possible use of the footprints we leave as we use our credit cards or surf the internet grows, since those footprints can be recorded and analyzed (Whitaker, 1999Whitaker, Reg (1999), The end of privacy. How total surveillance is becoming a reality, New York, The New Press.).

Although the relationship between safety and surveillance is an openly debated topic, and it is often argued there is a positive correlation between both of them[1], what does not usually come to the fore as clearly is the connection between certain control strategies and some spatial configurations, which in this manner become devices to exercise power and are effective, to a great extent, because they go unnoticed (Foucault, 1981Foucault, Michel (1981), Un diálogo sobre el poder, Madrid, Alianza Editorial., p. 37).

Such connections have a distant origin, and it is possible to trace some strategies from the modern age to this day, as they acquire a relatively different nature. It seems no researcher would now deny there have been profound changes starting in the last decades of the 20th century which are now shaping a new mode of development.[2] Some have called this development informational, others postmodern, others post-Fordist economy, etc.

Bauman uses the phrase liquid society or liquid modernity to highlight the rapid transformation of social forms, which are modified or disappear before becoming established being replaced by new ones. In this context, uncertainty becomes a basic trait, which leads to the formulation of the concept of liquid surveillance as typical of this period and in contrast to the Panopticon paradigm, which he describes as solid surveillance (Bauman and Lyon, 2013Bauman, Zygmunt and Lyon, David (2013), Liquid Surveillance, Cambridge, Polity Press.). In broad terms, this second view was characterized by a centralization of the guard, while the subjects under surveillance were forced to occupy a position where they could be supervised. On the contrary, and from Bauman’s point of view, in the system prevailing in our times which he calls liquid, the figure of the guard fades and the subject of surveillance itself accepts and even propitiates the interference in his or her private life sphere.

This is undoubtedly a rather suggestive analytical scheme, and one which can be helpful to understand certain contemporary phenomena. It is, at the same time, possible to introduce some qualifications which will allow a more complex and precise view of reality, and which in our opinion would be useful to understand certain spatial configurations, as well as the relationship between constructive morphologies and the supervisory functions entrusted to some buildings.

It is undeniable that the surveillance of an inmate in a 19th century prison was quite different from that conducted on us nowadays through the traces we leave in our everyday lives, whether by using credit cards, making searches on Google, etc. It would be important to qualify those differences with an approach that, without forgetting the great changes that characterize this post-modernity, paid attention to the continuities.

From this perspective, we could talk about a surveillance that aims to get involved with the objects of surveillance, modifying their attitudes or their will. Today not only are the prisons more populated than before, but in certain locations there are many relatively irregular detention centers or facilities for the confinement of immigrants, to cite some examples. In all of them, surveillance is concentrated, and the subjects of surveillance are confined in certain locations in order to be better controlled, with the aim of modifying or annulling them. We could call this device “coercive surveillance”, and it is also present in a pervasive way in our social fabric.

Furthermore, there is a supervision whose goal it is to find out traits or characteristics of individuals or groups, which will be processed and used for activities as diverse as police persecution or product sales. The amount of ads constantly popping up in our personal computers as a result of our internet history, or the configuration of risk groups by the police can exemplify these control systems we could call “inquisitive surveillance” (Fraile, 2014Fraile, Pedro (2014), "Arquitectura, espacio y control: morfologías, ciudades y vigilancias (siglos XVI-XVIII)". In: Casals, Vicenç; Bonastra, Quim (eds.), Espacios de control y regulación social. Ciudad, territorio y poder (siglos XVII-XX), Barcelona, Ediciones del Serbal, pp. 19-44.). Both forms coexist in our world, and are frequently combined, in varying proportions, configuring each concrete instance of surveillance, which can vary in composition over time, so that each specific act can have its own evolution depending on diverse environmental conditions.

From this point of view, control over a certain number of individuals is closely related to spatial morphologies and organizations, and the analysis of this relationship can be performed at different scales.

The organization of the State and its administrative and territorial restructure in many of the European countries during this transition into modernity is proof of that relationship between spatial configuration and population control.[3] Also along these lines can be interpreted the concern with capital status and jobs corresponding to certain cities. Throughout the 18th century there was a profuse production of literature on Policy Science (Fraile, 1997Fraile, Pedro (1997), La otra ciudad del Rey. Ciencia de Policía y organización urbana en España, Madrid, Celeste., 1998Fraile, Pedro (1998), "Putting order into the cities: the evolution of ‘policy science’ in eighteenth-century Spain", Urban History, 25 (1), pp. 22-35.), which dealt with urban management and the mechanisms to control the inhabitants of a city (Delamare, 1705-1738Delamare, Nicolas (1705-1738), Traité de la Police, où l’on trouvera l’Histoire de son établissement, les functions et le prerogatives de ses magistrats. Toutes les loix et tous les reglemens qui la concernent, Paris, M. Brunet.; Fraile, 2010Fraile, Pedro (2010), "The Construction of the Idea of the City in Early Modern Europe: Pérez de Herrera and Nicolas Delamare", Journal of Urban History, 36 (5), pp. 685-708.). In all these cases, the relationship between spatial configuration, surveillance and molding the conduct of those inhabitants is clear.

Finally, the building is the last level in this change of scales, and there too can be seen this link between morphology and supervision. In these pages we will focus on this scale, and in order to do that, we will look at some facilities with a clear function of surveillance and control, such as prisons. These, however, will not be the only buildings we will examine, as quarantine stations and Casas de Misericordia (Church-run institutions halfway between a hospice and a hospital) to cite some examples, also had similar functions, and as we will demonstrate, there was a continuum spanning different facilities, both regarding their functions and morphologies, which did not fully consolidate until mid 19th century, and in some cases even later.

Our starting point will be the 16th century, a time of profound economic and social transformations, and a milestone in the configuration of the main European cities and the urban network (Benevolo, 1993Benevolo, Leonardo (1993), La ciudad europea, Barcelona, Editorial Crítica.). At that moment, the work to be done in certain establishments was somewhat vaguely defined, which manifested itself in the oscillations of building structures and their constant change from one category to another. We will end our work in the first half of the 19th century, a moment when enlightened thought and the preceding evolution had contributed to a specialization of medical and penitentiary discourse, and to the fixation of building morphologies. This does not mean that reflection on this category of establishments ceased, but rather that it acquired a new dynamic as a consequence of the new conditions. In this review we will look at most of Europe, although we will pay special attention to the case of Spain. We will therefore pay attention to diverse institutions, and not only those dedicated to the punitive deprivation of freedom, although we intend to contribute to their history.[4]

THE PHASE OF MORPHOLOGICAL TRANSFERS (15TH-18TH CENTURIES) Top

The Renaissance brought about great changes both in the economy and social structure of Europe. There were also changes in the instruments of control and ideological regulation, which made for a new situation in which the main European cities were consolidated while in them grew the number of the poor or marginalized who straddled the line between a life of beggary and petty crime[5]. Seventeenth-century Spanish literature drew with precision the profile of the pícaro, a rascally knave who used his wits to make a living on the streets.[6]

This segment of the population, which developing commercial and productive structures were incapable of absorbing, went on to join the ranks of the destitute, and became a problem both for health and public order.[7]

The evolution in hospital architecture

Confrontational positions regarding poverty between Reformation and Counter Reformation are well known and, frequently, some historiographical schools of thought have insisted on the idea that Protestantism gave rise to more efficient practices in the management of marginalization. On the other hand, authors such as Linda Martz (Martz, 1983Martz, Linda (1983), Poverty and Welfare in Habsburg Spain: The example of Toledo, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.), following on Brian Pullan’s work on Venice (Pullan, 1971Pullan, Brian (1971), Rich and poor in Renaissance Venice, Oxford, Blackwell., 1976Pullan, Brian (1976), "Catholics and the poor in Early Modern Europe", Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, XXVI, pp. 15-34, 5th series.), have called into question this interpretation, and have shown the coherence in some of the poverty policies adopted by Catholic countries. In the case of Spain, the humanist ideology of Erasmus of Rotterdam played an important role and produced outstanding results, such as Luis Vives’ De subventione pauperum, originally published in Bruges in 1526[8]. At the time, there was in Europe a proliferation of regulations trying to impose some sort of order on charity giving and beggary, such as those from Nuremberg, 1522, Strasbourg, 1523, or Ypres, 1525, as well as the Edict of Ghent from 1531, or the later one from 1540, both referring to the sphere of the Spanish empire. The relevance of the problem and the pressing character of the situation had as a consequence the construction of a specific discourse (Fraile, 2005Fraile, Pedro (2005), El vigilante de la atalaya. La génesis de los espacios de control en los albores del capitalismo, Lleida, Milenio., chap. 3-4; Martz, 1983Martz, Linda (1983), Poverty and Welfare in Habsburg Spain: The example of Toledo, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press., pp. 12-34), one of whose central questions was the convenience, or absence thereof, of the creation of establishments destined to gather this segment of the population and adapt it to the new social and productive conditions. The idea of such establishments, which had received diverse names such as Hospitals, Casas de Misericordia, Charity Homes, among others, was not a novel one. Literature about such institutions abounds[9], and in general terms, the established prototype is the Renaissance hospital designed by Antonio Averlino (Filarete) for Milan in the 15th century. It consists of two buildings arranged as a Greek cross, one for men and one for women, both included in one same enclosure. Such a structure was not original, and had some prominent precedents, such as Santa Maria Nuova in Florence.

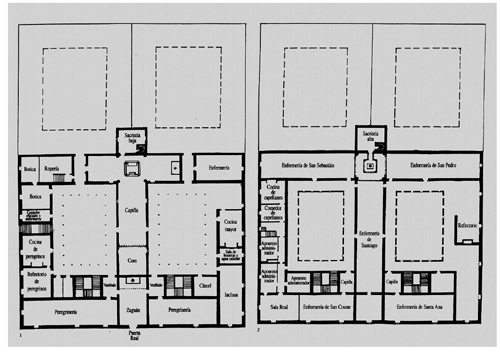

In the case of Spain, this building pattern was followed for the construction of a series of facilities during the times of the Catholic Monarchs[10], the best known being that in Santiago de Compostela (Fig. 1), the one in Granada, and the one in Toledo, all of them by the Egas brothers[11]. Their construction was key for the reorganization of those cities which, for different reasons, had acquired capital importance for the Crown. That is why Félez Lubelza, when talking about Granada, refers to these building works as a matter of State, fundamental in the construction of the Modern State the Catholic Monarchs wanted (Félez Lubelza, 1979Félez Lubelza, Fernando (1979), El Hospital de Granada. Los comienzos de la arquitectura pública, Granada, Universidad de Granada., p. 8).

|

Figure 1. Egas brothers, Hospital Real, Santiago de Compostela, 15th century, ground floor and level above. Rosende Valdés, 1999Rosende Valdés, Andrés Antonio (1999), El Grande y Real Hospital de Santiago de Compostela, Madrid, Electra-Consorcio de Santiago., p. 18.

[Descargar tamaño completo]

| |

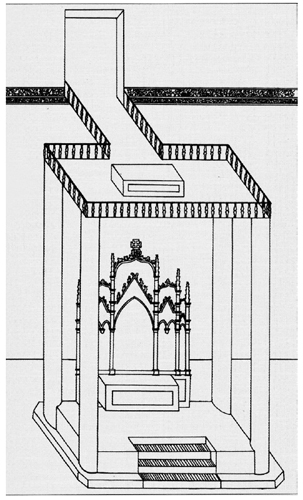

They were buildings planned as a Greek cross, with the hospital chapel at the crossing, right at the center of the plan. This was a place with high symbolic value, and the focal point of attention for all the people confined in the facility. In some cases, as in Santiago de Compostela, this aspect received special attention, since that was the location of a double altar (Fig. 2), the lower one visible to visitors who attended the place on holidays, while the upper one, which appeared to the inmates to be suspended in the air, was destined to make an impression on said inmates’ state of mind.

|

Figure 2. Egas brothers, Hospital Real, Santiago de Compostela, 15th century, central double altar, Rosende Valdés, Rosende Valdés, 1999Rosende Valdés, Andrés Antonio (1999), El Grande y Real Hospital de Santiago de Compostela, Madrid, Electra-Consorcio de Santiago., p. 46.

[Descargar tamaño completo]

| |

This structure survived for quite a long time, but towards the end of the 16th century it underwent a radical change influenced, no doubt, by several factors such as the remarkable changes in the treatment of poverty following the Council of Trent (Martz, 1983Martz, Linda (1983), Poverty and Welfare in Habsburg Spain: The example of Toledo, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press., pp. 45 and following.) Furthermore, during the 16th century the trend towards substituting bigger institutions which could fulfill different welfare functions for multiple smaller hospitals had been gaining ground (Martz, 1983Martz, Linda (1983), Poverty and Welfare in Habsburg Spain: The example of Toledo, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press., pp. 61 and following). Examples of such bigger facilities are the one in Tarragona or the Patio Manning in Barcelona, among others, many of which followed the will of the private donors who had contributed to their establishment (Español, 2014Español, Francesca (2014), "La tutela espiritual de los enfermos y su marco arquitectonico. Advocaciones y escenarios culturales en los hospitales de la Corona de Aragón en la Edad Media". In: Huguet-Termes, Teresa; Verdés-Pijoan, Pere et al. (eds.), Ciudad y hospital en el Occidente europeo (1300-1700), Lleida, Milenio, pp. 365-399.; Conejo da Pena, 2014Conejo da Pena, Antoni (2014), "Llum, noblesa, ornament, laor, glòria e amplitud: los hospitales y la renovada imagen de la ciudad bajomedieval". In: Huguet-Termes, Teresa; Verdés-Pijoan, Pere et al. (eds.), Ciudad y hospital en el Occidente europeo (1300-1700), Lleida, Milenio, pp. 415-445.).

Those years were marked by crisis in Spain, and the consequent increase in marginalization. Around 1575, difficulties were related to Philip II of Spain’s financial problems. It was then that clergyman Miguel Giginta published, between 1579 and 1587[12], a series of books in which he proposed the State undertake a welfare reform, while he traveled around the country trying to elicit support for his plan.

Later on, near the turn of the century, one calamity followed another: the Spanish Armada was defeated, and the plague ravaged the country with its resulting decrease in population. There was finally an awareness of the crisis. Under those circumstances emerged the works of Cristóbal Pérez de Herrera (1598Pérez de Herrera, Cristóbal (1598), Discurso del amparo de los legítimos pobres, Madrid, Luis Sánchez.)[13], a physician interested in works of charity who claimed to follow the clergyman’s ideas regarding welfare reform.

Giginta started from the existing architectural pattern: the Greek cross plan, but radically changed its meaning by making the crossing a center of permanent surveillance. Let us read his words:

The inmates are to be distributed in different refectories and dormitories, as said, level and without any partitions or hanging objects, each in their own bed and with their lamps on at night. And the administrator’s house must have a room over the crossing chapel, with small latticed windows overlooking each room, so that from any of them could be seen at all times whatever happened in said rooms: in this way, moving a foot, playing, eating, fighting, commotions or any other activity would not go on unseen. The lattices will make them think someone is behind them watching, and the watched areas being so well lit and clear, everybody will be visible to the rest, like supervisors and spies for the administrator, so that they will perforce be peaceful, although distrust of the latticework may already achieve that all by itself (Giginta, 1579Giginta, Miguel de (1579), Tractado del remedio de pobres, Coimbra, Antonio de Mariz Impresor y Librero de la Universidad., p. 39 overleaf).

We find ourselves before the discovery of central surveillance in facilities of this kind. Moreover, this surveillance must be continuous, and the inmates must not know whether the watchman is in the tower or not, so that the tower itself becomes the watchman, just as Bentham would propose for his Panopticon some 200 years later.

This is where two key elements of confinement come together: the chapel and the surveillance center. Power, control, and religiosity join forces, and this trinity permeates through the inmate’s daily life.

Some years later, Pérez de Herrera followed up on this model by defining a system with a classification into wings, thus building on what the clergyman had outlined.

The disciplinary regime proposed by Giginta is coherent with his scheme for total surveillance. In order to break the inmates’ will it is necessary to control their every move, their small actions, and to reduce the unruly ones through a system of mild, progressive and inexorable punishments.

In this establishment, which represents the beginning of central surveillance and a new mode of using spatial organization to control the individual, we find the two types of surveillance we initially mentioned: inquisitive surveillance, inasmuch as inmates are classified and constantly observed, and coercive surveillance, because knowing who the inmates are and how they act, it becomes possible to influence their will through work and a strict disciplinary system in order to change their conduct and attitudes. Furthermore, Giginta intends to induce behaviors in society as a whole by exhibiting poverty in an organized spectacle distributed throughout the urban landscape, something with clear precedents in certain ceremonies such as processions with the participation of brotherhoods of the poor (Raufast Chico, 2014Raufast Chico, Miquel (2014), "Las ceremonias de la caridad: asistencia, marginación y pobreza en el escenario urbano bajomedieval". In: Huguet-Termes, Teresa; Verdés-Pijoan, Pere et al. (eds.), Ciudad y hospital en el Occidente europeo (1300-1700), Lleida, Milenio, pp. 447-464.).

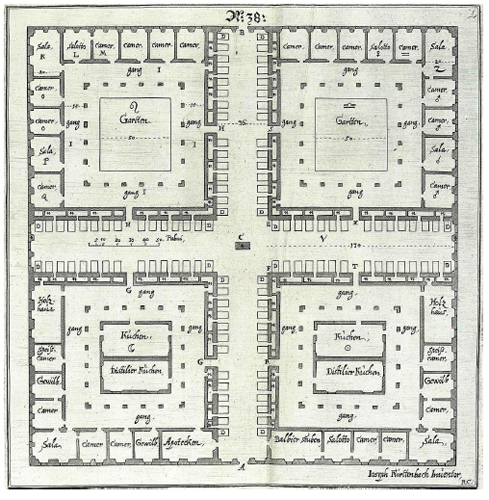

It is worth pointing out that this structure will be maintained during the 17th century, with small variations, and be applied to Hospitals or Casas de Misericordia, but on the contrary, central surveillance seems to be forgotten, and the building functions again with the initial dynamics established by Filarete. Multiple examples could be cited, like Ph. Delorme’s proposal from 1626 (Delorme, 1626Delorme, Philibert (1626), Oeuvre entière, Paris, R. Chandiere.)[14], or that of Furttenbach’s in his Architectura Civilis (1628), where we see facilities (Fig. 3) he describes “in the Italian style” with the beds distributed on the radii, and an altar placed at the center. Front yards are taken up by facilities, and backyards by gardens through which the different rooms can be accessed. Significantly, this architect used this pattern for such disparate buildings as schools and stables, but did not use it in his design for a prison.

|

Figure 3. Furttenbach, Joseph, Hospital Project, 1628. Furttenbach, 1628Furttenbach, Joseph (1628), Architectura Civilis, 2 vols., Ulm, Jonam Saurn., vol. II, Illustration 38.

[Descargar tamaño completo]

| |

This diagram makes it easy to think of adding more radii to increase capacity. One of the first projects in this direction was Antoine Desgodets’ (also Desgodetz) (Desgodets, 1716-1728Desgodets, Antoine (1716-1728), Oeuvres de Desgodets. Traité des ordres de l’architecture (1716-1728), manuscript from Bibliothèque Nationale de France.) towards the end of the 17th century, which had eight wings and a central chimney to facilitate ventilation (Fig. 4), a plan which must have made an impact at the time, since years later Tenon mentions it in his report (Tenon, 1788Tenon, Jacques (1788), Mémoires sur les hôpitaux de Paris, Paris, Chez Royez.) on hospitals, and its influence is clear in the proposal by Petit we will discuss below.

Along the same lines we find other hospitals, such as Sturm’s (Sturm, 1720Sturm, Leonhard Christoph (1720), Vollständige Anweisung Allerhand Oeffentliche Zucht-und Liebeg-Gebände, Aubsburg, J. Wolff.), and this trend continued until the debate that followed the fire at the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris in 1772, which prompted a reassessment of the principles governing this kind of institution. Thus, in 1777 Jacques Necker, Director General of Finance for the French government, encouraged the commission in charge of analyzing the means to develop Paris’ hospitals and to make improvements on the Hôtel-Dieu, which had to be done through a public tender for proposals. This call for proposals was very successful, receiving more than 150 submissions based on medical knowledge and the real needs of the practice of medicine, both factors that defined the hospital’s design, size and operation (Greenbaum, 1975Greenbaum, Louis S. (1975), "‘Measure of civilization’: The Hospital Thought of Jacques Tenon on the Eve of the French Revolution", Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 24 (1), pp. 43-56., pp. 44-46). Illness could no longer be mixed with poverty or vagrancy, so hospitals lost their function as welfare-providing institutions, and began to function strictly as health care facilities (Barret Kriegel, 1979Barret Kriegel, Blandine (1979), "L’hôpital comme équipement”". In: Foucault, Michel et al. (eds.), Les machines à guérir (aux origines de l’hôpital moderne), Bruxelles, Pierre Mardaga, pp. 19-30., p. 28). At the spatial level, various elements converged in this systematization, which were to configure the new hospital paradigm: the maintenance of fresh clean air inside the building and a care for its general salubriousness, the division into different units for the different kinds of diseases and patients, the functional separation of the hospital’s different services, and finally, attention to the problem of internal circulation flows (Fortier, 1979Fortier, Bruno (1979), "Le camp et la forteresse inversée". In: Foucault, Michel et al. (eds.), Les machines à guérir (aux origines de l’hôpital moderne), Bruxelles, Pierre Mardaga, pp. 45-49., p. 47-48).

A decision had to be made between the two basic models submitted as proposals for the new building: a radial model and a model based on a pavilion system, the former submitted by Coquéau, Poyet and Petit, the latter by Le Roy. It is not surprising that the Commission des Hôpitaux chose Le Roy’s pavilion model proposal if we consider that during the selection process, a national survey was launched to gather observations from the Académie de Marine on ships, quarantine stations and military hospitals—in it superintendents were asked about the charitable institutions in each of their districts—, and that in 1787 the Commission sent Jacques Tenon and Charles Coulomb to England with the mission of surveying their facilities, some of which, like the naval facilities in Plymouth and Portsmouth already used this design. Furthermore, quarantine stations like the Nouvelles Infirmeries in Marseille had empirically arrived at a “pavilion model” solution avant la lettre through successive expansions and renovations of their facilities (Bonastra, 2008aBonastra, Quim (2008a), "Los orígenes del lazareto pabellonario: la arquitectura cuarentenaria en el cambio del setecientos al ochocientos", Asclepio: Revista de historia de la medicina y de la ciencia, 60 (1), pp. 237-266.). In this way, the adoption of this system meant, in the case of the hospitals, an end to the possibility of linking safety to surveillance (Fortier, 1979Fortier, Bruno (1979), "Le camp et la forteresse inversée". In: Foucault, Michel et al. (eds.), Les machines à guérir (aux origines de l’hôpital moderne), Bruxelles, Pierre Mardaga, pp. 45-49., p. 49).

Under those circumstances, what we have termed coercive surveillance takes on a different character, as it goes from acting on the individual to acting on a pathology. Likewise, inquisitive surveillance changes direction with this functional specialization, as only certain characteristics of the patient are of interest, namely those related to his ailment, so that the required information is obtained through strict classification, clinical history, etc. There is also a simultaneous change in scales, as this medicalization extends to the whole of society, over whom research and inquiries are systematized, while strategies are designed to act on the whole of the population in the name of public health (Foucault, 2004aFoucault, Michel (2004a), La naissance de la biopolitique. Cours au Collège de France (1978-1979), Paris, Seuil.).

At that time we find in Spain a similar tension between both systems. On one hand, the ninth volume of Benito Bails’ Elementos de Matemática (1772-1783Bails, Benito (1772-1783), Elementos de Matemática, 9 vols., Madrid, Viuda de D. Joachin Ibarra.) is published, and it is dedicated to civil architecture. In it Bails uses as the model for hospitals the one presented in France in 1774 by Antoine Petit, which falls within the framework referred to above. In the section of actual constructions, the most ambitious radial hospital erected in Spanish territories is the Hospital de Belén in Guadalajara, Mexico, built between 1787 and 1797, whose patient wards take up seven of the eight radii of a great star, leaving the last radius for the church (Bonet Correa, 1967Bonet Correa, Antonio (1967), "El hospital de Belén, en Guadalajara (México), y los edificios de planta estrellada", Archivo Español de Arte, 40 (157), pp. 15-46.). On the opposing side of the argument, the construction of a quarantine station in Mahón is authorized in 1787, and it is built following the pavilion model of the Nouvelles Infirmeries of Marseille. This was the first example of the pavilion model for quarantine stations which were to be so important during the 19th century (Bonastra, 2008aBonastra, Quim (2008a), "Los orígenes del lazareto pabellonario: la arquitectura cuarentenaria en el cambio del setecientos al ochocientos", Asclepio: Revista de historia de la medicina y de la ciencia, 60 (1), pp. 237-266.). In 1793 the enlightened Valentín de Foronda translated into Spanish and published the third report of the Commission des Hôpitaux (Lassone, 1786Lassone, Joseph-Marie-François de et al. (1786), "Troisième Rapport des Commissaires chargés, par l’Académie, de l’examen des projets relatifs à l’établissement des quatre Hôpitaux", Historie de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, pp. 13-43.) relative to pavilion-system hospitals (Foronda, 1793Foronda, Valentín de (1793), Memorias leídas en la Real Academia de Ciencias de París sobre la edificación de hospitales y traducidas al castellano por Valentín de Foronda, Madrid, Imp. Manuel González.), introducing in Spain the new model arising from the debate that followed the fire at the Hôtel-Dieu.

Prison typologies

During the 17th century and good part of the 18th century, many prisons and facilities of that kind used all sorts of structures. We should take into account that the specific discourse on prison regimes that characterized the Enlightenment and substantially changed the legal and regulatory framework, through contributions of Montesquieu, Beccaria or Lardizábal among others, had yet to be developed[15]. Therefore, there wasn’t a coherent reflection on the function of confinement, or on the facilities which should serve to that end. Regardless, architects such as Alberti, Filarete, Palladio or later Ledoux could not help but refer to them, but none of them made novel proposals, nor did they establish successful models. In general terms, their main line of arguments revolved around the exterior appearance of the buildings and the sober and severe image they should project. It should not be forgotten that until well into the 19th century, it was common practice to re-purpose buildings such as convents and barracks for these uses.

If we look at some of the cases explained by J. Howard (1777Howard, John (1777), State of the prisons in England and Wales, Warrington, W. Eyres.), we find facilities like the prison in Newgate (1770), or the House of Corrections, a juvenile correctional institution in Rome (1705), where the radial scheme is not used. Likewise, Furttenbach (1635Furttenbach, Joseph (1635), Architectura Universalis, Ulm, Johann Sebastian Medern.), who had made abundant use of that building model, seemed to forget it when he designed both his “small prison” and his “large prison” (Fig. 5), which has three confinement categories, and where control is exerted by a guard who walks among the cells. The cells here are isolated units on one same floor plan, an original solution.

It is not until the late 18th century that we get the radial plan of Ghent prison (Fig. 6), by architects Malfaison and Kluchman. In it had been established a classification regime in the different trapezoids, but there was no central surveillance system, strictly speaking. Pevsner has said it is probable that the plan might have been copied directly from that of the hospitals, and argues that in the Mercure de France a radial hospital design by Pierre Gabriel Bugniet had been published in 1765, inspired by the designs of Desgodets or Sturm, and it in turn oriented the work of the Ghent architects (Pevsner, 1980Pevsner, Nikolaus (1980), Historia de las tipologías arquitectónicas, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili., p. 192). Moreover, the debate over hospital morphologies we have mentioned had begun during those years, and it had considerable influence while the different models were being looked at, among them Petit’s radial model, which was widely disseminated.

Shortly thereafter, amid this climate of reflection on building structures, on the role of custodial sentences and, as a consequence, on discipline, order, and surveillance, came Bentham’s Panopticon, when conditions were ripe at the end of the 18th century for the acceptance of central surveillance, a formula proposed almost 200 years earlier. Later, the combination of central surveillance with the widely known radial floor plans gave way to prisons of this kind, of which there were many in the 19th century, and some of which are still in operation today.

Compromise for a hybrid facility: quarantine stations

Among all these discourses and diverse solutions it must be mentioned that in the last decades of the 18th century and the first of the 19th, some quarantine station projects offered a solution of compromise between both extremes of the debate. Quarantine stations have often been defined as spaces half-way between a prison and a hospital. A hybrid space sharing part of the spatial logic of both institutions, but with an obvious logic of its own related to incubation periods of epidemic diseases and to the transported goods’ capability to harbor the influence of the plague (Bonastra, 2010bBonastra, Quim (2010b), "Recintos sanitarios y espacios de control. Un estudio morfológico de la arquitectura cuarentenaria", Dynamis, 30, pp. 17-40.).

The quarantine station projects we examine here date from 1786 and 1826. They were designed by Pomepo Schiantarelli and Giuliano de Fazio respectively, to serve the ports of Mesina and Napoli[16]. The building by de Fazio is a reformulation of Schiantarelli’s, of whom he had been a disciple. In both of them can be observed a compromise between the pavilion system, which offers a space for classification—compartmentalized, isolated, well-ventilated and easy to walk around—and the centralized surveillance of the panoptic radial prisons. Ideas regarding medicine and penology are mutually reinforced in one same institution, their will to cure and correct blend in a building whose purpose is neither the former, since a quarantine station only assesses the health conditions of its users, nor the latter, because forced confinement notwithstanding, it only tries to stop a potential epidemic.

We thus find the features of both institutions, segregated departments, one for those contagious and one for observation, enclosures separated by walls for each vessel’s crew and cargo, and discrimination between people and goods within each of the enclosures. In both cases, all of this in one space with a central octagonal structure simultaneously allowing the multiplication of separate spaces and centralized surveillance from the tower at the center of this star. This tower served as a centrifugal surveillance point in the panoptic style, to provide victuals and other necessities to the inmates, and as a centripetal point concentrating the attention of the faithful towards the chapel. The top of the walls served as a path for the guards keeping watch to walk on, allowing a peripheral surveillance complement typical of the pavilion-style quarantine stations.

None of these facilities was ever built, but mentioning them is important because of the ingenious structural solution they offered, combining both typologies in tension at the end of the 18th century. They remind us of the solution adopted in Ghent, and of both types of surveillance, coercive as regards the radial disposition with its complement of peripheral surveillance, and inquisitive, related to the compartmentalization and segregation imposed by the pavilions. Moreover, this project modality was not wasted, at least in the kingdom of the Two Sicilies, as evidenced by the prison in Avellino, in the middle of the Campania province, which was finished in 1837 and was designed by de Fazio himself, or the Ucciardone prison in Palermo, by Emmanuelle Palazzotto, which opened in 1842.

We have so far shown the fluidity and the transfer of the different construction models among facilities destined to control their inhabitants. As both institutions, prison and hospital, defined their functions through specific reflection, the former specialized in legal confinement, whereas the latter became medicalized, a process which solidified their architectural models.

In all cases, in every event of surveillance we see a combination of the two types, inquisitive and coercive.

THE DEBATE DURING THE ENLIGHTENMENT AND ITS REALIZATIONS IN SPAIN Top

At the end of the 18th century, the Enlightenment started a wide debate on the very organization of society and the State, and public health and punishment were part of that reflection.

The prisons

Authors such as Montesquieu, Rousseau, Beccaria, or Lardizábal in Spain, among many others, wrote on the function of legal punishment, on the form it should adopt, and the tasks it should perform, and made fragmentation of time the key to providing a penalty to the crime (Trinidad, 1991Trinidad, Pedro (1991), La defensa de la sociedad. Cárcel y delincuencia en España (siglos XVIII-XX), Madrid, Alianza Editorial., ch. II). Legal confinement, and consequently prison, became the prototype for punishment, and the very building acquired a new perspective, which in part explains Bentham’s Panopticon, or the great debate about the internal regulations of prisons. This is how experiences such as the Philadelphia prison, run by Quakers, were conceived.

Penitentiary discourse did not happen at a theoretical level only, such as in the discourse of philosophers like Montesquieu or Beccaria, it also influenced the practice. In this sense, the works of Howard marked a milestone and were an unavoidable reference point in the debate about penitentiary reform, a movement taking place all over Europe and in the United States. It would be impossible to summarize such complex dynamics in these pages, or to mention the interventions it caused, but we shall deal with the most significant works published about this in Spain, which defined trends and had a certain influence on the architectural projects launched afterwards.

We will mainly concern ourselves with three works which follow a temporal and conceptual progression. We will discuss Arquellada’s translation of Rochefoucauld-Liancourt’s works on the Philadelphia experience, where the issue of internal regulations is discussed while the architectural aspects are barely mentioned. Then we will focus on the work of Marcial Antonio López, in part inspired by Howard, as it reviews the main facilities at the beginning of the 18th century and lays down some building criteria. Finally, we will address the works of Villanova y Jordán, where he deals with the realizations of the projects, proposing a reformed Panopticon, according to the author more useful and adaptable to Spain. All these works follow a chronological order while also following a progression from the general to the specific.

La Rochefoucauld, duke of Liancourt, (1795/6 (An IVLa Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, François-Alexandre-Frédéric duc de (An IV), Des prisons de Philadelphie, par un Européen, Paris, Du Pont.) was a prominent thinker and philanthropist, the founder of a model farm, a school of Arts and Crafts, and even a Savings Bank, being concerned about mendicancy, charity, and prisons. With the Revolution he immigrated to North America, and a result of this experience was his Des prisons de Philadelphie. The book was later translated into Spanish by Ventura Arquellada (1801Arquellada, Ventura de (1801), Noticia de las cárceles de Filadelfia: escrita en francés por La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, Madrid, Imp. Real.) under the auspices of the Count of Miranda, President of the Real Asociación de Caballeros, an organization providing aid to inmates of the prisons of Madrid, where he himself acted as secretary. In his work, published in 1801, Arquellada doesn’t only translate La Rochefoucauld, but adds an Appendix where he explains in rather laudatory terms the advances achieved in Spain regarding penitentiary reform, and mainly as they related to the associations working to aid the inmates.

The Frenchman’s work deals with the regime instituted by the Quakers at the Philadelphia prison towards the end of the 18th century. It therefore precedes the reform which later resulted in the star-shaped building which has become the symbol for that prison model. The virtues of solitary confinement are expounded, and the effects it has on the inmate’s mood when paired with discipline and work. Throughout his work, La Rochefoucauld insists on the importance of knowing the offender, his crime and his attitude, to be able to act and have influence on him. We see here the influence of the two kinds of surveillance we have mentioned: inquisitive and coercive.

Although references to the importance of order, cleanliness and discipline are constant throughout his work, spatial proposals are scarce, and are limited to some considerations on the solitary confinement cells which are described as “eight feet long by six feet wide, and nine feet in height” (Arquellada, 1801Arquellada, Ventura de (1801), Noticia de las cárceles de Filadelfia: escrita en francés por La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, Madrid, Imp. Real., p. 11).

Common rooms, holding from ten to 12 beds, are furnished with all necessities, and of work places he says: “workshops for rough work are in the courtyard, and those for finer work are located in rooms on the same level as dormitories, but in another part of the building” (Arquellada, 1801Arquellada, Ventura de (1801), Noticia de las cárceles de Filadelfia: escrita en francés por La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, Madrid, Imp. Real., p. 23).

The history of this establishment is well known, as is the fact that at the beginning of the 19th century, when it became too small and inadequate for the imposed regime, a public contest was announced, which English architect John Haviland won, and its result was the star-shaped building associated with this confinement regime.

In his Appendix, Arquellada insists on Spain’s achievements in relation to prison reform and the treatment of inmates, but the situation could not be so good if when referring to the Cárcel de Villa de Madrid he paints such a desolate picture. Such a situation could not be exceptional, reason for the constant debate on the convenience of penitentiary reform and how to carry it out. In fact, it seems it was rather the norm if we are to believe the documented work done towards the end of that century by Major Arthur Griffiths, inspector of prisons in Great Britain, where he remarks on the unsatisfactory conditions of most correctional facilities and prisons of the State (Griffiths, 1991Griffiths, Arthur (1991), In Spanish Prisons. The Inquisition at Home and Abroad. Prisons Past and Present, New York, Dorset Press., pp. 123-149).

Another important milestone in this reflection is the work of Marcial Antonio López, a character of political and intellectual relevance concerned by the social problems of his time. In 1832 he published in Valencia his work Descripción de los más célebres establecimientos penales de Europa y los Estados Unidos (A Description of the Most Famous Penal Institutions of Europe and the United States), in two volumes.

In the first volume he goes over the objectives that should be pursued by incarcerating offenders, and the general criteria that should govern said incarceration. In the second volume he deals with some of the practical aspects, such as the architectural design of prisons.

In his approach he fundamentally follows the guidelines proposed by the reformers of the time. He quotes Howard, Bentham, Buxton, and Cunningham among others in very favorable terms, and mentions reports such as the one written in France about the state of penitentiary facilities. From this perspective he defines the objectives of the new prisons:

Relief for a multitude of unfortunate wretches, their improvement, the exact fulfillment of their sentences, a greater scale of penalties so that no crime remains unpunished, and ultimately, the wellbeing, safety, satisfaction, and the economy of the State (López, 1832López, Marcial Antonio (1832), Descripción de los más célebres establecimientos penales de Europa y los Estado Unidos, 2 vols., Valencia, B. Montfort., vol. 1, pp. 29-30).

It is easy to recognize the ideas of Montesquieu, Beccaria, Lardizábal or Howard in these words. Essential to achieving these goals are discipline, surveillance, and controlled activity. Regarding the first one he says:

By inspection of the inmates (...) I mean supervision at all times, in such a way that it covers their behavior, their speech, and all objects of their thought. This supervision affords their guards an intimate knowledge of the inmate’s moral state (López, 1832López, Marcial Antonio (1832), Descripción de los más célebres establecimientos penales de Europa y los Estado Unidos, 2 vols., Valencia, B. Montfort., vol. 1, p. 155).

He then mentions the need for continuous inspection, which he extends to subordinates, with the object of modeling the attitude and behavior of all those converging in the prison space. Once again we find inquisitive and coercive surveillance.

The complement of this constant supervision is the activity and control of all the individual’s smallest actions, what Foucault called the policy of detail[17], which tends to control the bodies, and finds here a clear formulation:

The cleaning regime has a higher purpose (...) A link has been observed between physical and moral frailty (...) The efforts to achieve cleanliness serve as stimulus against laziness, they give the person an appreciation of circumspection, and teach a respect for decency even in the smallest things. Moral and physical purity have a common language (López, 1832López, Marcial Antonio (1832), Descripción de los más célebres establecimientos penales de Europa y los Estado Unidos, 2 vols., Valencia, B. Montfort., vol. 1, p. 83).

Throughout this first volume, following Howard’s model, he describes different facilities, pointing out their exemplary aspects, as well as the defects he deems worth mentioning.

It is in the second volume where he looks at the realizations of those ideas, starting with the buildings and their location, aspects where he follows Bentham and Howard. Regarding the location, he proposes the facilities be built outside the cities, but not far from them, to facilitate communication and provision of supplies. They should be erected in a salubrious location, as per the hygienist principles of the time, although he also suggests, in line with Bentham’s ideas, the creation of other establishments to house ex convicts until their full reincorporation to society. He calls these facilities Reconciliation Homes, and those could be built closer to the city.

He dedicates a chapter to Bentham’s Panopticon, translating full excerpts from his work, but introducing some modifications we will mention later. Obviously, he defends central inspection, although he ultimately favors the radial structure rather than Bentham’s double building. This is how he explains his idea:

It is a building whose bodies or main parts form radii originating from a common center. On the different floors of this center are located the superintendent’s quarters, the offices common to the whole prison, and the chapel. From his room, the superintendent can inspect the different courtyards, workshops, rooms, and leisure areas, and instantly reach any of those parts (López, 1832López, Marcial Antonio (1832), Descripción de los más célebres establecimientos penales de Europa y los Estado Unidos, 2 vols., Valencia, B. Montfort., vol. 2, pp. 54-55).

Marcial Antonio López ascribes this model to what he calls the “Royal London Society of Prisons”. If we take into account that his works were published in 1832, it is fair to assume that this kind of building was already well known, so it is not strange that in 1821 John Haviland designed a building of these characteristics for the new Philadelphia prison. About the facade and general ornamentation he agrees with Bentham on the convenience of a sober and severe appearance, as well as on the importance of making an impression on the visitors’ spirits.

In spite of following Bentham so closely, he refines some aspects that he considers are not examined in depth in the works of the Englishman, and should be taken into account for their application in Spain. For example, he makes the following proposals: buildings to be located a short distance from urban areas; buildings to be built by the convicts themselves after an outer wall has been erected by free construction workers; the use of non-combustible materials, such as stone, brick or iron; hallways wider than those proposed by Bentham, and greater separation between the central tower and the ring-shaped building (which would improve lighting and ventilation, the greater space created inside could be destined to different uses); it would be convenient to study the water circulation system (including a sort of heating system); designate spaces for workshops, store rooms, and school, preferably on the ground floor; define a precise location and shape for the latrines.

He then addresses some building aspects for which he provides general criteria, such as the infirmary or the individual cells. Of note is his proposal to replace regular rooftops with flat roofs, with the proper slant to allow for the collection of rain water, but still appropriate for other uses.

Finally, although he does not expressly suggest it, he seems to favor the idea of model facilities. He proposes the creation of a great majestic center in Madrid, concentrating different categories of imprisonment. It would be the place to conduct experiments, make course corrections, and it would serve as example for anything that was built afterwards.

In Marcial Antonio López’s work a series of criteria tending towards the radial model are laid down which would have future impact, but this is done while introducing precisions and clarifications for the construction of possible panopticons.

To conclude this review of the early 19th century discourse on prison architecture, we should look at Jacobo Villanova y Jordán’s Aplicación de la Panóptica de J. Bentham (1834Villanova y Jordán, Jacobo (1834), Aplicación de la Panóptica de J. Bentham a las cárceles y casas de corrección de España, Madrid, Imp. de T. Jordán.), which includes noteworthy realizations and was, in a way, the culmination of the process. This author, a Criminal Prosecutor for the Royal Court of Burgos, was responsible for promoting penitentiary reform at the beginning of the Trienio Liberal (1820–1823), when a parliamentary commission was created for that purpose.

This book was published at a time of complex dynamics. The Real Asociación de Caballeros for the aid of inmates had already presented a prison project, with its budget and plan (now disappeared) supposedly drawn by Juan Antonio Cuervo (Ramos Vázquez, 2013Ramos Vázquez, Isabel (2013), La reforma penitenciaria en la historia contemporánea española, Madrid, Dikynson., p. 82). Later, in 1819, as Villanova himself explains to us in the introduction to his book, he conveyed another project to the Crown, together with a model, through the mediation of the Marquis of Casa-Irujo, and it was then sent to the Madrid Economic Society, where it was the subject of a very positive report. Unfortunately nothing came of it, and in 1833 he sent it again to Francisco Fernández del Pino, then Minister of Justice. After several ups and downs, as the author explains, his work was filed and almost disappeared, until he recovered and published it in 1834. We don’t know where the model ended up, and it would have contributed to our understanding of his proposals, but the plan is included (Fig. 8) in his book, where he shows how it diverges from Bentham’s original idea, and where Marcial Antonio López’s earlier reflections can be traced.

It is significant that both the report from the Madrid Economic Society and the author point out that the building could also serve as a hospital. On the subject of hospitals, Villanova says: “(Bentham) has profited from the experiments done with hospitals” (Villanova y Jordán, 1834Villanova y Jordán, Jacobo (1834), Aplicación de la Panóptica de J. Bentham a las cárceles y casas de corrección de España, Madrid, Imp. de T. Jordán., p. 31).

Here we also find repeated the arguments given by Marcial Antonio López on the objectives of the reform, the importance of surveillance, and of controlling the inmates’ everyday lives, sometimes in almost the same words. For example, when discussing hygiene: “A link has been observed between physical and moral frailty (...) Moral and physical purity have a common language” (Villanova y Jordán, 1834Villanova y Jordán, Jacobo (1834), Aplicación de la Panóptica de J. Bentham a las cárceles y casas de corrección de España, Madrid, Imp. de T. Jordán., p. 73).

We will now go over his points, some of which depart from Bentham’s original plan. Among them we should point out important differences such as those related to the different seclusion categories, since, as can be seen in the plan, there are two kinds of rooms. In the rectangular rooms (c) are the “communicated inmates”. The rooms should house four, six, or more individuals. Trapezoid rooms were destined, some (d, from 1 to 6) to solitary confinement, and the rest (e) would be used as store rooms and for other purposes.

Villanova echoes some of Marcial Antonio López’s ideas. He pays special attention to the latrines (f), situated at the back of trapezoid rooms and with a lateral access from the rectangular rooms for communicated inmates.

Our author also proposes that regular rooftops be replaced by flat-top roofs built with the appropriate inclination to collect rain water, which could be used—through a system of pipes (g, h)— to clean the latrines. By making the higher levels of the building accessible, he assigns them different functions, although mainly he suggests they be used as a courtyard for walking, the elevation making the area well ventilated and particularly healthy. The part corresponding to the central tower should serve to house the altar for religious services. It would not be permanent, but rather be taken down like a portable field altar.

He enlarges the space between the different buildings, so that being larger than in Bentham’s model it could be used as a courtyard or for other purposes.

In his proposal, the facilities are surrounded by two walls, the first one shaped as a circle, and the second one as a square. The first line (p) creates a crown which could be used to house water deposits and an orchard to provide the prison with its own produce.

He widens the hallways (b) to ease the transport of some materials and to improve lighting.

Ultimately, the central surveillance criteria typical of the Panopticon remain untouched, and the building structure is followed, albeit with the incorporation of some details which, in his opinion, were not clearly defined in the Englishman’s work.

Hospitals and quarantine stations

Although from the end of the 18th century and during the first half of the following century Spanish prisons clearly followed the central surveillance trend, mainly adopting radial or panoptic solutions, hospitals and quarantine stations tended to follow the pavilion model.

As we have seen, in the case of quarantine stations, the one in Mahón started this tradition by following the guidelines of Marseille’s Nouvelles Infirmeries at the height of the debate on the new hospital model we mentioned before. Furthermore, Valentín de Foronda’s translation of the third report from the Commission des Hôpitaux (Fig. 9) also helped make the pavilion model better known. However, in both cases this remained, as a consequence of the scarce building activity in the health care field, a theoretical introduction until the late 19th century, due to various reasons of unequal weight. On the one hand was the endemic lack of funds to invest in this kind of facilities. In the case of quarantine stations, in spite of the proliferation of projects throughout the 18th century, and of the tax levied in order to build them in the most important ports of the country, funds were repeatedly diverted to other ends deemed more urgent by the government (Bonastra, 2010aBonastra, Quim (2010a), "El largo camino hacia Mahón. La creación de la red cuarentenaria española en el siglo XVIII". In: López Mora, Fernando (ed.), Modernidad, ciudadanía, desviaciones y desigualdades, Córdoba, Ediciones de la Universidad de Córdoba, pp. 453-472., pp. 453-472). It should be considered that since the end of the 18th century Spain experienced deep economic crisis, made worse by the war effort of the Independence War, and a national Treasury in crisis[18]. On the other hand, during the first decades of the century, an important body of opinion against the existence of hospitals and in favor of home care grew both among influential physicians and within the ranks of the political class. This thinking was well established at the time of the Trienio Liberal, and was favored by the government of Ferdinand VII, with the foreseeable consequence of a delay in the evolution of hospitals as centers for the development of medicine, and in their final separation from poorhouses, which was already under way in France and England (Cardona, 2005Cardona, Álvaro (2005), La salud pública en España durante el Trienio Liberal, 1820-1823, Madrid, CSIC., pp. 101-138). To all of that we must add that the disentailment of several ecclesiastical properties which took place during that period left many convents and other kinds of buildings in the hands of public institutions. These buildings were converted into hospitals, insane asylums or prisons in a liberal way as regarded the architectural requirements for the proper functioning of such facilities.

Nevertheless, the pavilion model triumphed in Spain in these initial decades of the 19th century when it came to designing hospitals and quarantine stations, even if these designs never reached the building stage. As has been widely studied, the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts was the entity in charge of controlling access to the Architect profession, and of evaluating and sanctioning public construction works. Connected to other European academies, it followed carefully all advances in the field, the reason it became an access point for all new building trends. For instance, the Academy was interested from the beginning in the debate started in Paris over hospital typologies after the fire at the Hôtel-Dieu, committed as it was to adapting traditions to the new uses assigned to buildings (Santamaría, 2000Santamaría, Rosario (2000), La tipología hospitalaria española en la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (1814-1875), Tesis doctoral, UNED., p. 351).

During the first half of the century, no pavilion-style hospitals were built—Madrid’s Hospital de la Princesa, the first built in Spain, was opened in 1857—and references to these were almost nonexistent in the literature on architecture or medicine produced in Spain. In 1847, notable hygienist Pedro Felipe Monlau barely addressed the issue in his famous treatise on public health, taking for granted that “infirmaries should consist of isolated pavilions on a field or garden, reduced to one room at ground level and another above it, with twelve or fifteen patients at the most in each room” (Monlau, 1847Monlau, Pedro Felipe (1847), Elementos de Higiene Pública, Barcelona, Imprenta de D. Pablo Riera., p. 44). Despite all this, pavilions became a symbol of modernity and innovation regarding architectural typologies for hospitals and quarantine stations.

This triumph becomes more evident if we take into account the papers and projects elaborated during exams at the San Fernando Academy by the applicants for the titles of Academician of Merit and Architect during the first half of the 19th century[19]. The heading of one of the possible exam papers for the period that concerns us was: “Dissertation on the local situation of hospitals in a Court, which should be taken into account for their comfortable use, ventilation, and insulation from contagious diseases”. This statement shows how avant-garde the Academy was in various aspects: in contemplating the location, and by being aware of the new needs of modern hospitals, where disease was no longer mixed with poverty.

An analysis of the projects presented by candidates to both professional bodies shows their knowledge of those presented before the Paris Academy of Sciences, about which the enlightened Valentín de Foronda had informed in his Spanish translation of the third report from the French Commission des Hôpitaux.

We should also consider that, during the first decades of the 19th century, Spanish students had access to two relevant texts besides the classic architecture manuals. Benito Bails’, mentioned before in this paper, who espoused the radial solution for hospitals and copied word for word the writings of Antoine Petit for his Paris proposal, and Francisco Antonio Valzania’s text, who in a veiled way argued for isolated pavilions (Valzania, 1792Valzania, Francisco Antonio (1792), Instituciones de Arquitectura, Madrid, Imprenta de Sancha., pp. 62-66).

Thus, both among the candidates for Academician of Merit and for Architect, it is clear there is a trend to embrace modernity, as represented by the pavilion typology, be it in its purest form, with isolated buildings within a rectangular enclosure, a profusion of patios and gardens, or be it as a hybrid form, with pavilions dedicated to infirmaries attached to a central body housing administration and services. Regardless, we should bear in mind that applicants to the first category did not have to draw plans, so we have only their written arguments to follow and therefore get a less precise idea when compared to the applicants to the title of Architect, who did have to draw plans. Among the hospital typologies seen in these exams, we can highlight classic palatial structures, cross-shaped structures, and in only one case a star-shaped structure in the Petit style.

Another sign of innovation was, in the case of Academicians of Merit, the choice in favor of hospital decentralization, as the majority of them proposed the construction of small facilities meant for a reduced number of patients for the treatment of different ailments. In this way, the buildings would be spread around in the vicinities of the urban area, but separate from it, with the double purpose of ensuring the wellbeing of the facilities’ users, avoiding city noise and enjoying the fresh air of the countryside, and simultaneously protecting the city from the putrid smells patients or the building as a whole could give off (Santamaría, 2000Santamaría, Rosario (2000), La tipología hospitalaria española en la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (1814-1875), Tesis doctoral, UNED., chaps 6-7). Monlau was of the same opinion, he assured it was better for the hospitals to be small and specialized in one illness only, or in the case of big hospitals, that there were separate rooms dedicated to different illnesses (Monlau, 1847Monlau, Pedro Felipe (1847), Elementos de Higiene Pública, Barcelona, Imprenta de D. Pablo Riera., p. 44). This contrasted with the hospital idea that had prevailed in the Academy during the preceding century in the times before the fire at the Hôtel-Dieu, as evidenced by the official announcement for the architecture awards of 1760, where the first class prize mentioned “A great hospital...” or, during the debate about hospitals in the city of Paris when the title was “A great Hospice...” (V.V.A.A., 1992V.V.A.A. (1992), Hacia una nueva idea de la Arquitectura. Premios generales de Arquitectura en la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (1753-1831), Madrid, RABASF., p. 61, p. 101). In both cases can be discerned the idea of a great infrastructure preceding the separation of hospitals from hospices.

As we have mentioned, the introduction of the pavilion model for hospitals implied the loss of priority for surveillance. With the medicalization of this institution, inquisitive surveillance took precedence over coercive surveillance inside the facilities, since what mattered was maintaining the good health of the social body.

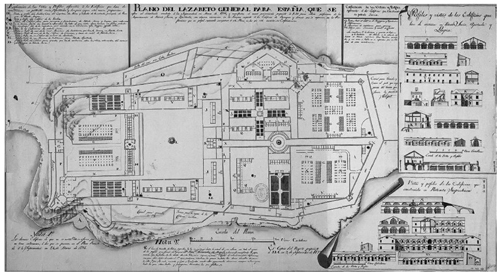

As regards quarantine stations, we have seen that the 18th century ended with the order to erect the huge complex in Mahón (Fig. 10), meant to be the general quarantine station for the whole kingdom. Its design was based on the Nouvelles Infirmeries of Marseille (Fernández de Angulo, 1786Fernández de Angulo, Francisco (1786), Ydea del proyecto de un Lazareto general de Cuarentena en el Puerto de Mahon Ysla de Menorca, Servicio Histórico Militar, exp. 12.892, sig. 3-3-1-5.), and it was the first in all of Europe to be built in the pavilion style. In this case, this was possibly due to the existence of a clear referent coupled with the greater need for quarantine facilities than for hospitals.

|

Figure 10. Fernández de Angulo, Francisco, Plan for the Quarantine Station in Mahón (Menorca), 1794. Servicio Histórico Militar, 3588-17.

[Descargar tamaño completo]

| |

The San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts became again a source of capital importance to see how the pavilion model entered into the design of Spanish quarantine stations, both because of its architectural competitions (the first class prize in 1805 asked for the design of “three separate quarantine stations for Madrid”), as well as for the exams it set to obtain the degree of Architect. In any case, the model’s success in the Academy’s projects was less than in the case of hospital projects, in spite of Mahón’s being one of the most modern in Europe, and an example of the new building technologies.

Furthermore, in contrast with the smaller facilities that were now the trend for hospitals, the Academy’s quarantine stations were excessively big for the standards of the time, going well over the dimensions of the quarantine station at Mahón, of the building proposed by Howard in his famous work on quarantine stations[20], of those in the Rapport by Hély D’Oissel (1822Hély d’Oissel, Abdon-Patrocle (1822), Rapport sur l’établissement de nouveaux lazarets, adopté par la commission sanitaire formée près le ministère de l’Intérieur, Paris, Imprimerie Royale.) or the works of Bruyère (1828Bruyère, Louis (1828), "Esquisse d’une petite ville maritime et Essai sur les lazarets. Xe Recueil". In: Bruyère, Louis, Études relatives à l’art des constructions, recueillies par Louis Bruyère, 2 vols., Paris, Chez Bance ainé.), to name a few examples of the references which may have been used by the authors of those projects.

Spanish literature on hospitals, except for that generated by the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts competitions, was scarce. On the other hand there was much more abundant literature about quarantine stations. This preeminence is explained by the fact that in this first half of the 19th century the dreaded plague was still spreading in the Orient, and the yellow fever and cholera made their appearance, reviving the debate on the need to provide the Spanish coast with preventive infrastructures against imported epidemics whose vectors were still mostly unknown. These health threats made many politicians and doctors favor quarantine measures in spite of the growing liberalism in most countries, and of the way quarantine measures hindered trade.

Spanish works about the architecture and layout of quarantine stations were mainly written by doctors. One example is the one written by Minorca physician Manuel Rodríguez de Villalpando (1813Rodríguez de Villalpando, Manuel (1813), Lazareto de Mahón ó Memoria descriptiva de sus obras, Mahón, Serra.) about the quarantine station in Mahón, where he recorded specifications about its layout four years after its opening. As a curiosity, his text does not include even one mention of the word pavilions. Manuel Casal (1832Casal y Aguado, Manuel (1832), La epidemia pestilencial en general. Discurso médico-político sobre se esencia, definición, conocimiento, causas, signos precursores, remedios, precauciones &c, según los dictámenes y observaciones de los mejores autores que la tratan contagiosa, Madrid, Imprenta de Don Norberto Llirenci.), in his volume about Epidemia pestilencial en general (The plague epidemic in general) (1832), proposed that four quarantine stations were set up in Madrid, to match the idea of the above mentioned Academy prize, but featuring the hospital decentralization we have made reference to before (Casal, 1832Casal y Aguado, Manuel (1832), La epidemia pestilencial en general. Discurso médico-político sobre se esencia, definición, conocimiento, causas, signos precursores, remedios, precauciones &c, según los dictámenes y observaciones de los mejores autores que la tratan contagiosa, Madrid, Imprenta de Don Norberto Llirenci., pp. 53-54). In spite of that, there is no mention of pavilions.

Of interest in relation to yellow fever is the series of quarantine stations—about which there are many written references—built or projected with the common denominator of using temporary facilities consisting of wooden cabins or camping tents, emulating the layout of quarantine stations such as Mahón’s. Among them, we have the facilities described by Tadeo Lafuente in 1805Lafuente, Tadeo (1805), Observaciones justificadas y decisivas sobre que la fiebre amarilla pierde dentro de una choza toda su fuerza contagiante, Madrid, Imprenta Real., consisting of isolated huts distant about eight or ten yards from each other. Or the writings by an anonymous Majorcan author about a plan to preserve from and cure contagious diseases, and for whom quarantine stations should “consist of wooden barracks or tents, in each of the three main divisions destined to convalescent patients, suspected patients, and fumigations” (Anonymous, 1820Anonymous (1820), Plan preservativo y curativo de las enfermedades contagiosas de Son Severa y Arta. Con un apéndice sobre lazaretos, Palma, Imprenta de Felipe Guasp.). We will finish with the description by another physician, Hernández Morejón, of his ideal quarantine station, which without a mention of the word pavilion, points clearly to a pavilion layout:

There must exist in it three huge departments, aired, with constant ventilation; with their own subdivisions to comfortably serve the three bills of health: suspected, foul, and touched. (...) It is also required that the same (the department for those with a suspected bill of health) have an infirmary for those affected by common not-plague-related illnesses, which must be perfectly ventilated, roomy and spacious. (...) The department for those with a foul bill of health will not differ at all from the suspected. The department for touched bill of health will only differ from the other two in the number of infirmaries, which will be three or four (Hernández Morejón, 1821Hernández Morejón, Rafael (1821), Memoria sobre el contagio en general, y en particular de perteneciente a la peste, calentura amarilla y fiebre pestilencial. Modo de construir útiles lazaretos, Mahón, Imprenta de Pablo Fabregues y Portella.).

When we turn our attention to the facilities that were actually constructed, the only quarantine station built during this period was that in San Simón, built in 1842 in the tidal inlet of Vigo and meant to be the Atlantic coast complement of the quarantine station in Mahón. It was made up of isolated pavilions, although the reduced size of the islands on which it was built did not allow for the physical separations so typical of this model. Nevertheless, its construction, together with that of Hospital de la Princesa a decade later, shows the triumph of the pavilion model in health care buildings.

This meant that here as well as in the case of hospitals, inquisitive surveillance was more important than coercive surveillance, although this did not mean coercive surveillance was absent. This is confirmed by the multiplication of quarantines, by the strict separation of arrivals depending on the danger posed by the different ports of origin, of the transported goods depending on their capacity to harbor the contagious disease, of the crews depending on their sanitary conditions, and on the different timings depending on the disease in question. All these precautions reach their zenith in the pavilion-style quarantine station. Finally, it is worth remembering that this kind of surveillance had always been more present in quarantine stations than in hospitals, at least until the inception of the process that medicalized hospitals, as inquisitive surveillance was at the very origin of the institution and the network of sanitary protection these stations were part of, with the information exchange on epidemics, informants at suspect locations, sanitary bills of health, interviews on arrival to ports, etc., which prefigured this greater interest in the health of the social body.

CONCLUSIONS Top

Throughout these pages we have traced the evolution of the architectural structures of some buildings designed for the control of their occupants. We have done so based on the idea that each instance of surveillance combines two ways of performing it: one we have called inquisitive, whose objective is to gather and systematize information about its inhabitants, and coercive surveillance, tending to influence their attitudes through the management of their everyday lives.

We have pointed at the discovery of central surveillance in radial structures already in the second half of the 16th century, in institutions called Casas de Misericordia, which were a cross between a hospital and a center for housing marginalized people and the poor. This radial structure was used profusely in many buildings for almost two hundred years, in that institution with vague functions called Hospital. In the meantime, central surveillance practically disappeared from these establishments, and became rare in prisons, which were mostly built following other models, rarely star-shaped.

During this time, quarantine stations, a hybrid institution blending forced seclusion and sanitary performance, acquired forms which combined pavilion and radial solutions.

In the second half of the 18th century, the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution brought about specific reflections both on the functions of legal punishment and legal systems, as well as on the functions of medicine. As a consequence, some morphologies became more established, as they answered to the tasks performed in the different buildings and these tasks were being more precisely defined. This process clearly shows the link between the different structures and their form and function. Where the function was related to punishment, central surveillance—which had a clear paradigm in Bentham’s Panopticon—gained ground in Europe, and radial structures proliferated.